When it came to teaching the MX world a lesson, Husqvarna’s 400 Cross was top of the class.

Words and pics: Tim Britton

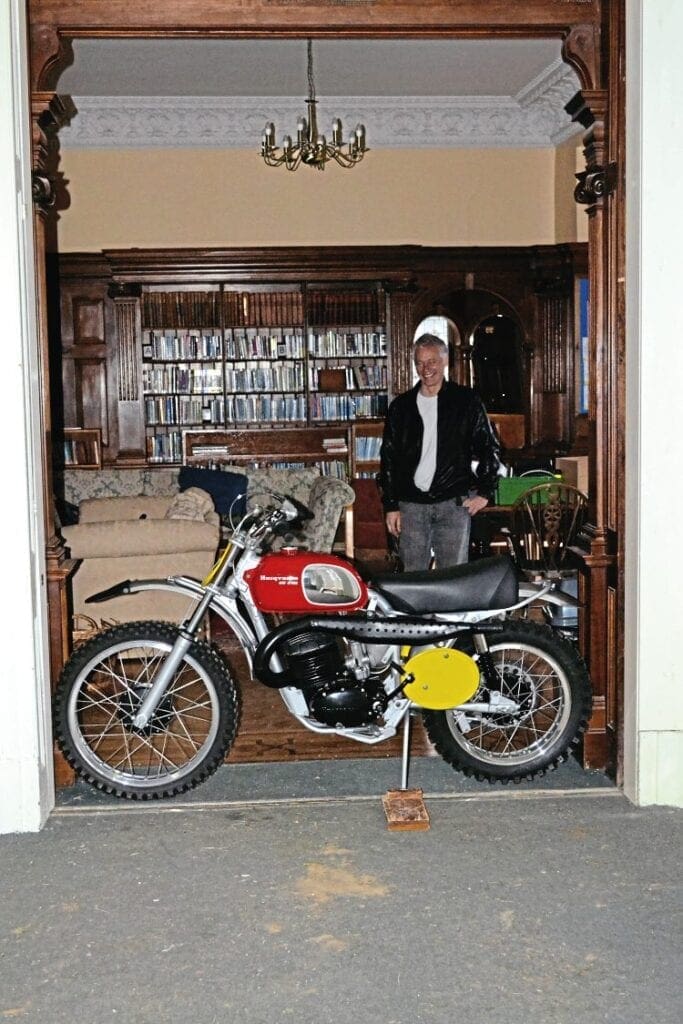

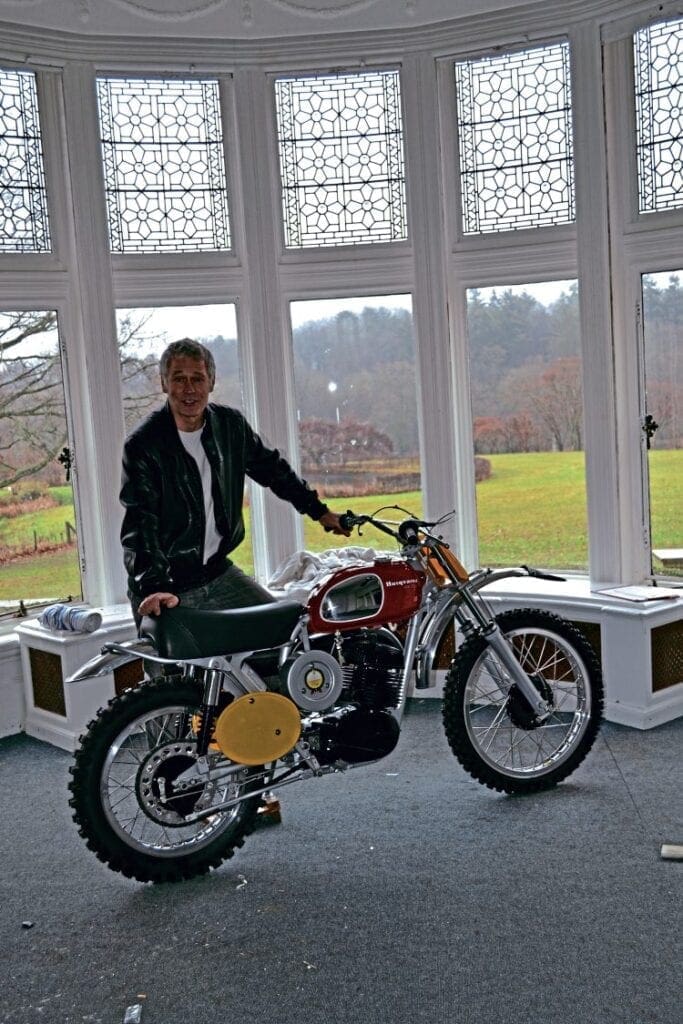

Looking at Will Bennett’s bike again, after its Stafford-winning appearance, it was clear this was still a superb machine.

A photoshoot planned for December is fraught with difficulty, the weather being the major problem as it could be so bright as to make photography difficult, so cold as to make standing around uncomfortable or, as in this case, so wet and miserable we nearly had to call the whole thing off.

It didn’t help that the weather forecast was telling us it was clear and bright in Kent.

“I could ring the school to see if we can do the shoot in our workshops,” said tech teacher Will. With the school officially on Christmas break, or the pupils at least, this seemed a great idea, so with the bike safely in the van, off we went round a very rural Kent, to St Ronan’s School.

Parking outside its grand exterior Will and I left the Huskyin the van while we went to make our presence known to the school office.

Following the principle of nothing ventured nothing gained, I asked if there was a possibility of doing the shoot inside the school… which is how we ended up wheeling a Swedish motorcycle through the halls of an English prep school.

Will looked on incredulously as I waffled on about light and contrasts with the pastels of the room enhancing the red, silver and black scheme of the 400 Cross. I could tell he wasn’t convinced, but he mellowed when he saw the photos.

Looking at this 400 Cross, it is hard to believe it didn’t start out as a complete bike. The bare bones were there – rolling chassis and engine, or most of the engine anyway – but there were a lot of parts to source.

“That is the bit which really took the time,” says our man, “I was determined to find the correct bits to make the bike as catalogue as possible, if I’d been building it to ride then this would have been of less concern, but I’ve another Husky to race.”

It was then he admitted he’d been smitten by the 400 Cross since seeing a scale model kit of one when he was young. “I’ve become a bit of an internet auction site hound,” he grins, as his phone bleeped with warnings of parts auctions coming to an end.

Will had clearly immersed himself in Husky lore and his dedication to the accuracy of the restoration extended to trying to source Swedish ‘Bufo’ fasteners which were the original equipment suppliers to Volvo as well as Husqvarna. These fasteners are particularly rare and even an internet search didn’t help, but rumour has it Scania Trucks use them.

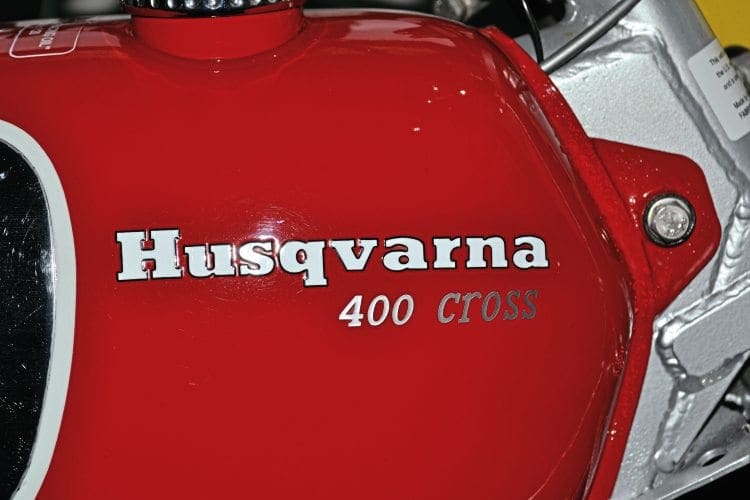

Also rare is the ‘for one season only’ petrol tank, it’s the same shape as the season before and after, but for some reason the cap is off-set to the right-hand side as the rider sees the bike. Why? Who knows, we don’t. This wouldn’t be a major problem if it was unobtainable as the tank is only steel and the position could be moved, but the right one turned up.

Also missing were the contents of the gearbox and the exhaust system. Gearbox bits weren’t a problem as Will knows a man… the exhaust pipe however, was the last year of the bolt-on manifold and to get one undamaged is probably out of the question, but an acceptable one did eventually turn up.

Also turning up with a stroke of luck was the sidestand and a genuine Renold chain.

With parts coming together, Will felt able to start the rebuild, or at least look at the frame to see if it needed repair, and it did.

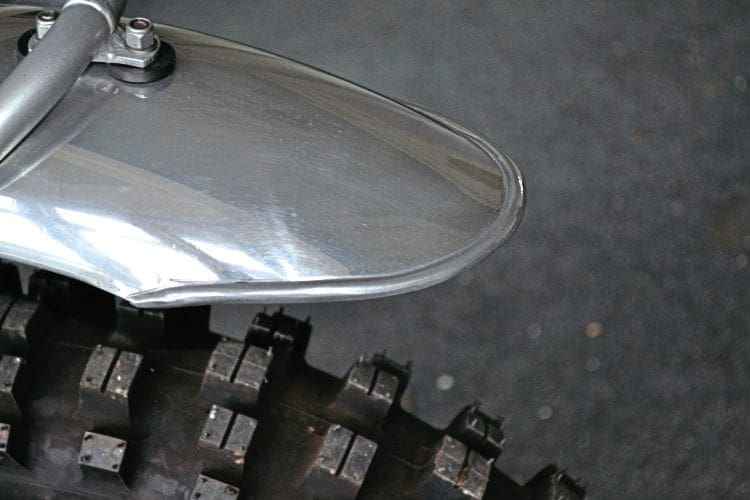

Apparently the subframes always need repair and the support plates where it joins the main frame have a bush which wears out, then the hole wears oval and needs welding and the bush replacing. Also the footrest mounting holes wear quickly so needwelding and remachining.

“I also set to and made the titanium swinging arm spindle… it cost more in dies to cut the thread than it did to buy the material in the first place,” he grins.

While talking about the chassis Will mentioned the front forks which are Husqvarna’s own make but were quite ropey.

“The chrome was pitted and the seals torn, so I had a word with HCP who wanted the sliders too when the stanchions were to be chromed. That meant I’d to refurbish them first.”

It seems not only are there seals in the top where you’d expect them, but also the bottom of the tube drifts out and there’s a seal in there too.

This was a difficult process and one Will doesn’t attempt any more as the seal is an odd size and took ages to find something suitable.

Once the sliders were done, the whole lot was shipped off to HCP so the hard chrome could be replaced. This is an engineering, rather than a decorative, process and involves accurate grinding and polishing of the stanchions after plating.

The thickness of the plating can be accurately controlled so it is possible to take up wear in sliders without replaceable bushes.

Okay, frame and forks sorted, rear suspension replaced with new Girling dampers, next up were the wheels.

For 1970 the 400 Cross came with Akront alloy rims and when the wheels were stripped at Sid’s Wheels the rims were deemed okay so repolished, the hubs and brake plates only needed blasting, stove enamelling and new bearings before Sid respoked them with stainless spokes.

The original brake shoes were fine and went back in. Tyres and tubes are Mitas and while modern are sort of period.

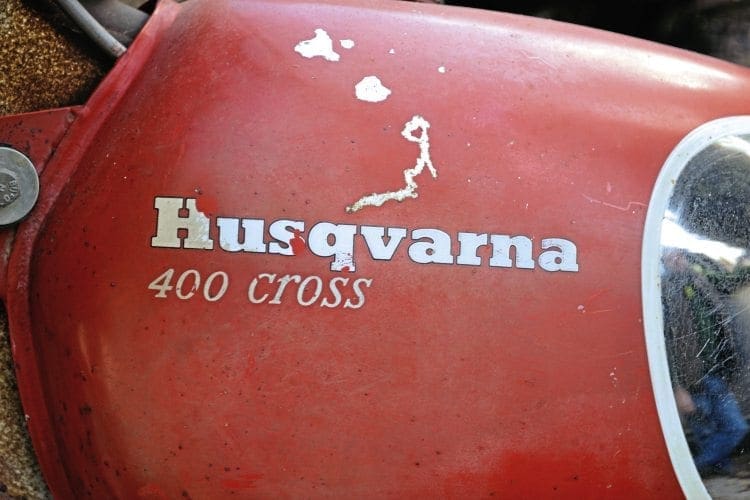

One of the most easily identifiable features of any Husky is the petrol tank and its bright red finish with polished side panels make the bike recognisable even before seeing the name.

Will handed his over to J P Tanks who knocked out a few dents before polishing and chroming the steel tank.

Once plated, the red finish – using Husky Club recommendations as to the exact colour – was applied over the chrome, while leaving the side panels clear and it seems there are templates available to make sure this is accurately done.

The name and model decals on the tank are new old stock (NOS) – originals. Compared to the tank, the seat was adoddle and needed only the base blasting, brackets reattaching and the originalfoam recovering for it to look superb.

With a rolling chassis to look at, Will was itching to get the engine sorted and determined the motor should not leak oil at all.

So, with grinding paste and a truly flat surface, he lapped the case faces until they were flat so when he assembled them, with a light smear of jointing compound, oil would stay where it was supposed to.

Naturally, all bearings have been replaced and the crankshaft has a new con rod kit in, a new over-size Mahle piston was found and the barrel bored to suit.

Once all the engineering bits were out of the way the cases, head and barrel could be stove enamelled to the closest match Will could find for the original finish.

This meant the major engine assembly could progress and the unit fitted into the frame before all the other bits were added, such as the primary drive and clutch.

Will showed me the drawings and photos of the clutch, pointing out the bush on which the clutch basket sits.

Despairing of finding one, Will went into the local bearing factory looking for material to make one; they took a look at the original, measured it and said how many do you want?

Will got a small batch for not a great lot of cash. Once it was pressed in place the clutch could be assembled with new plates – Surflex ones – and original springs… all 16 of them!

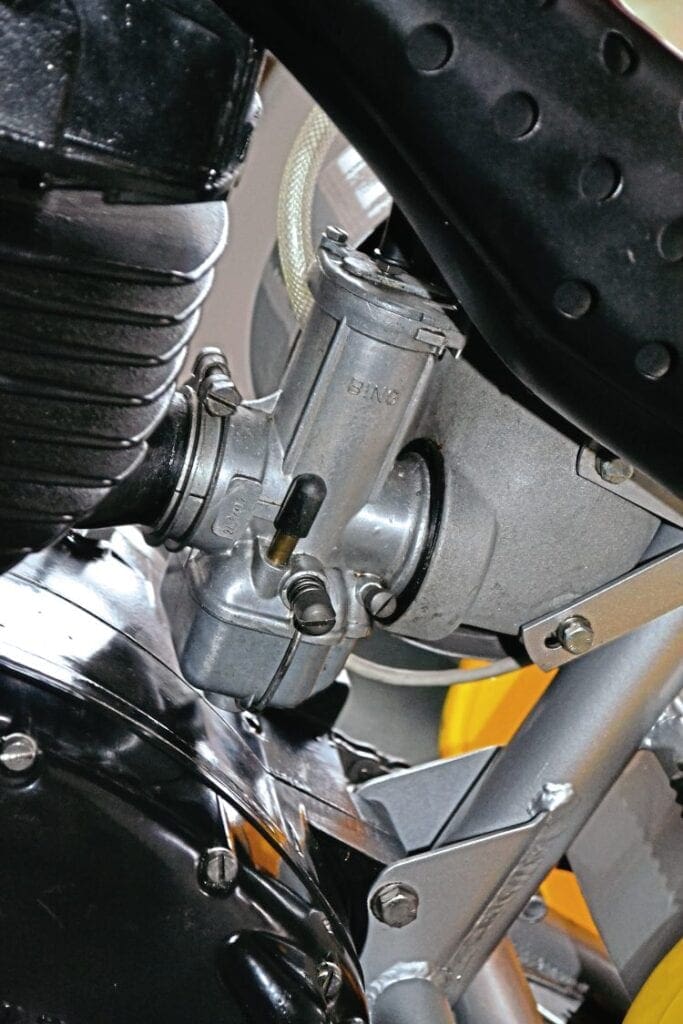

Now then, no matter how good a restoration is, without an ignition system it won’t work. Husqvarna used a Femsa system and with new points and condenser fitted there was a nice fat blue spark. Will even managed to find the correct grey sheathing for the wiring harness.

As I’m scribbling down his words (and anyone who’s seen my notepads will confirm, ‘scribble’ is the right word), I’m frantically trying to recall if I’ve asked him everything.

“Can’t think of anything else,” he says. We look at the bike again… “New ‘bars?” “No, the originals rechromed,” he says. After a few moments pondering:

“Oh, the only thing I’m not sure about is how the front brake cable would be held in place under the fork seal boot. If anyone knows, or can supply a pic, I’d like to see what it is like.”

As we stood looking at his bike, Will admitted he was pleased to have been given the accolade of winning best MX Machine at Stafford, but said he hadn’t done it with that aim and had only decided to enter at the last minute.

That said, it is a worthy winner and doubly so as the theme of the show was On Any Sunday where the iconic 400 Cross was ridden by an iconic movie star.

Edison Dye

Mention Husqvarna anywhere, but especially in the USA, and the human dynamo called Edison Dye will soon come up in conversation. It is likely that without his influence and sometimes crazy vision, the Swedish marque would have taken a lot longer to get going in the USA and it was all down to a chance meeting in a restaurant with a Swedish motorcycle dealer holidaying in Southern California.

It’s not that the company wasn’t known in the USA – it was, as there were riders who’d competed in the likes of the ISDT in Europe and seen the machines and how they went – but there was no coherent plan to import Husqvarna.

Initially the factory was not in favour of the idea either, there being no MX to speak of in the USA, but Dye wasn’t going to let that stop him and persuaded the factory to chance it.

One of his greatest flairs was for publicity and surely it can be no coincidence that where once Triumph were the movie stars’ bike of choice for the dirt, by the late Sixties it was Husqvarna. The bikes were ideal for the movies too, being glamorous and shiny, but they proved this was no make-up, they could perform too.

St Ronan’s School

I have to say that this school is by far the most incredible location for a photoshoot CDB has had for many a year, and of course we didn’t just turn up and start photographing a motorcycle in its superb interior.

The Husqvarna’s owner, Will Bennett, is a teacher at the school and it is thanks to him I had the surreal experience of wheeling a 1970 MX bike through the oak-panelled entrance, corridors and library to the language rooms overlooking the rugby pitch.

St Ronan’s School is located in Kent and is housed in what used to be the home of the Gunther family who, among other things, were behind the OXO brand.

Looking at the school’s website www.saintronans.co.uk and its historical section in particular, both the school and the building which is now its home have had an interesting life with the estate being listed as early as 13th century and the school being founded in 1883.

The two came together in 1945 and the estate is now in trust for St Ronan’s School. CDB extends its thanks to the headmaster and staff of St Ronan’s for allowing us access.

Who is Will Bennett

Will Bennett is a 53-year-old design technology teacher at St Ronan’s School in Kent.

A self-confessed Husqvarna nut with a serious addiction to the Swedish marque, his initial inspiration for the silver and red bikes was seeing a friend’s brother building a Revell model kit of the 400 Cross more years ago than he cares to remember.

His varied working career has included a spell as a cabinet maker and producing safety systems for the food, oil and nuclear industries.

His varied MX career has included some tasty Evo stuff and more than the odd Husqvarna, but started on a small Suzuki before graduating to TM and RM 125s then 250 Maico for AMCA Junior class where he won a bit here and there.

He’s dabbled in trials riding too and the only time, until now, he’s been mentioned in the press, is when he crashed an OSSA trials bike in an arena trial.

Original and unrestored

We’ve not had an original and unrestored bike in CDB for a few issues and we’d thought the supply had dried up, then, on a chance call to Charles Preston at Husqvarna Vintage, up pops this 400 Cross from 1970.

Just to remind you, the theme at Stafford in October for the Carole Nash Classic Motorcycle Mechanics Show was the all-time classic motorcycle movie On Any Sunday. Husqvarnas featured quite a lot in the film and star Steve McQueen was filmed riding a 400 Cross.

Charles had a 1970 machine we could borrow and it turned out to be completely original and unrestored. By a quirk of fate, Will Bennett decided at the last minute to bring along his fully restored 1970 400 Cross and the opportunity to have them both together in one feature was too good to miss.

Only problem being not much is known about the history of the bike, other than it is a genuine UK machine and an early version of the model range. Husqvarna, it seems, updated their bikes through the season so specification altered a little as the season wore on.

What is clear from a close inspection of the bike, is it’s likely never to have been raced. Charles told CDB he got hold of the bike at a farm sale and once back at his place with the carb cleaned out, some fresh oil in the engine and the bore lubed a bit, he persuaded the bike into life.

The reason for it having been laid up was soon clear… the main bearings were rumbling. The best guess is it had been used for some practice, the bearings started to fail and it was put to one side to be dealt with later and ‘later’ never arrived.

“It’s a great indicator of the era,” says Charles, “the worst damage is scuff marks whereas harder-used bikes will have dings and dents everywhere, maybe replacement bars and levers, this one is exactly as it would have been.”

With a bike in such a remarkably well preserved condition, there is the dilemma of should it be restored or should it be gently recommissioned and left with its patina of age. Personally, my thoughts are gentle recommissioning and retaining the patina of age but others may have a different idea.

With little real interest in MX from a management more concerned with volume sales, it was up to the riders themselves to modify existing machines into workable competition bikes.

This led to a cottage industry growing up around the base bikes and it was certainly possible to buy frames, forks, rear suspension, barrels of various capacities and better carburettors to make the original 175cc three-speed Silverpilen into a creditable race bike.

This didn’t mean the factory were unaware of what was needed, or even that they wouldn’t develop things, they did, and the factory riders had full 250cc engines for 1958.

However, a downturn in sales in general led to the factory deciding motorcycles were not viable and ceased production of the Silverpilen.

Problem was, the successes of the factory riders had created a demand, albeit small, for replicas of the team bikes.

A plan to produce moped engines in the region of 70,000 a year fell through, a factory facility built to accommodate this production was turned over to chainsaw and sewing machine manufacture, but there was room for MX engine production.

A plan was put together to make 100 machines for sale to prominent riders, the board were convinced only because the plan used stockpiled Silverpilen parts.

It turned out that the bike they built and the limited backup from the factory, was enough to allow Torsten Hallman to eventually become the first 250cc world MX champion.

Did the factory rush to embrace this success? No. But they did sanction the 100 models proposed and set the stall for future development.

Eventually, this led to the works machine-inspired 250 and 360cc models of 1968. Though excellent machines, the 360 was still underpowered for open class racing and a bigger engine was needed.

Initially this was a 420, but vibration and power problems meant it wasn’t as good as envisaged. A drop of capacity to 400cc with different bore and stroke ratios produced a machine to take on the world – the 400 Cross.

Read more News and Features online at www.classicdirtbike.com and in the latest issue of Classic Dirt Bike – on sale now!