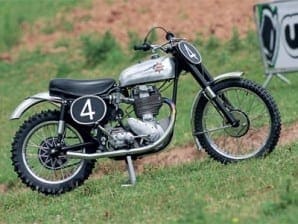

Our test bike was a 1955 scrambles model, built by Hilton Green as a tribute to his dad, Phil Green, who had raced mostly Goldies between 1948 and 1961. Bill Bottfield, an ex-Comerfords employee, helped to source parts for and and build this bike and it always amazes me the amount of people who, like me, have worked for or had some connection with the old Thames Ditton dealers.

Anyway, just why this single cylinder push rod motorcycle has iconic standing may be down to the success generated at scrambles and trials level by BSA thinking. This meant getting as many of the best riders in European, British and centre level to ride their motorcycles and the ensuing success would lead to a dominance of the sales market. Something my short period as a GP rider for BSA showed in 1971.

When team manager Brian Martin invited me to join a BSA team with John Banks, Dave Nicoll, Keith Hickman and another new signing, Andy Roberton, already on board, I said not all of us could be winning. He said this was true but to remember, if we were all on BSA then it was one less the opposition would have.

Development

The route to Gold for BSA began on 30 June 1937 at Brooklands race track near Weybridge in Surrey. Well known racer of the day, Wal Handley, arrived with a well prepared 497cc Empire Star for a Bemsee Club meeting and won a three lap race on the famous banked concrete track at an average speed of 102.47mph with a flying lap at 107.57mph.

The Bemsee club’s custom was to award a Gold Star to any rider who lapped Brooklands at 100mph or more in any of their races; Handley and BSA earned the coveted badge. With this success, designer Val Page set to work and there emerged in 1938 a new, super sporting 500cc single with cylinder and head in light alloy and an integral pushrod tunnel. In recognition of Wal Handley’s feat BSA named the model the M24 Gold Star, it sold for £82 10/-Post WWII the Goldie arrived in the range with a brazed and lugged plunger frame which was OK but not brilliant. One of Jeff Smith’s columns in Classic Dirt Bike pinpointed Bill Nicholson’s contribution to the development of the Gold Star up to the final year of production in 1963.

Bill Nicholson was from Northern Ireland and was friends with Rex McCandless, then experimenting with his revolutionary swinging arm rear suspension. They grafted on to the rear of a 1940 B29 McCandless suspension and Bill Nicholson rode his first scramble in 1946 winning the prestigious Cotswold event with ease, and changing development of motorcycles for ever.

At the factory, new boy Nicholson felt things could be improved. He wasn’t allowed to use his McCandless rear suspension but did develop a lightweight rigid frame for his trials bike that could have a swinging arm grafted on. Despite managerial opposition, Nicholson proved the concept in competition and laid the foundation for the Gold Star’s domination of scrambling.

It makes for fascinating reading how the bikes we bought in the era from a giant of a company like BSA for trials and scrambles were developed by one man driving his ideas forward. Sometimes alterations were carried out overnight after rushing back to Small Heath between events so new ideas could be tried next day, how sophisticated would these have been? My guess is not very but certainly practical when applied by the skills of Bill Nicholson.

It seemed the BSA competition department changed little from these early days to after the great triumphs of Jeff Smith winning two World Championships in 1964 and 1965. When I went to Small Heath to pick up my first bike, an ex-Keith Hickman GP bike, on a piece of waste ground at the back of the factory, Norman Hanks of the famous sidecar road race dynasty was one of the GP scrambles mechanics and took the bike on site.

The bike sounded a bit flat when started but Norman soon put things right, keep her running was the instruction and he wicked off the points cover and moved the ignition plate round a bit on the slots and declared it was now fine after a couple of blips on the throttle. Afterwards the handlebars had moved and with no spares available they just brazed the clamps to the handlebars in the right position and said they would be chromed before I returned to pick the bike up. So in the final year for BSA and the competition department there was still no sophistication only practical skills gleaned by racing men for racing men.

Early experiences

From a nine-year-old beginner on a 1914 Levis two-stroke until I finished my electrical apprenticeship at 21, my early motorcycling only provided two chances to ride a Gold Star.

I lived in Garlogie Bar, Aberdeenshire and the route through our village was often used by Joe Furneaux – an Aberdeen dealer/racer and George Christie who was about to start racing a Clubman Gold Star DB 34 – to test bikes. One day he asked if I would like to have a ride up and down the road only if I did not stall it as nobody was going to come and get me.

Once on I just kept slipping the clutch to get some speed up then change gear, just as well it was a mile long straight. Down past the old primary school I used to walk to and after about a ten point turn I came hurtling back pleased as punch with little knowledge I had just been riding such a sought after motorcycle of the future.

The next Gold Star was a 350cc scrambles bike owned and ridden by Aberdeen motorcycle dealer Les Shirlaw. Being in a farming community, we knew everyone for miles around and built ourselves a track with our club Bon Accord. We christened it Mosswood Park after Hawkstone Park and although the track is no longer there the Bon Accord Club is still flourishing and being driven by men like Brian Able and Ken Whittaker.

My Dot had broken, not an uncommon occurrence as our mechanical knowledge was nil, with Devoid of Trouble written on the tank having a kind of hollow ring to it. This 350cc Goldie felt fast as it was one of the few on methanol at the time. I was in the lead and enjoying the experience suddenly, there was an almighty bang and the con rod appeared out the bottom of the crankcases.

Not a happy Les muttered about over revving and I would have to visit the shop on Monday night after work to see what the damage was and what the cost would be. Petrified, as money was tight, Les and his father kept me strung along for ages and eventually told me it would probably have happened anyway but the funny thing is, I never got to ride it again.

End of the line

The Gold Star production run came to an end in 1963 but its contribution to the development of motorcycling was off the Richter scale. In the world of scrambling this model was ridden by all the greats in the 50s and 60s at some stage of their careers.

The most successful year for Gold Star scrambles machines must have been 1955 when Johnny Draper, the brother-in-law of Jeff Smith won the European Championship which started in 1952 and became the World Championship in 1957. Johnny Draper was first and Swedes Bill Nilsson and Sten Lundin were second and third, all riding BSA Gold Stars. The Moto Cross de Nations in Denmark was won by Sweden with Bill Nilsson, Sten Lundin, Lars Gustafsson and Gunnar Johansson all riding Gold Stars.

Jeff Smith was undoubtedly the most successful Gold Star rider, winning the best individual performance at the Motocross des Nations in Denmark in 1955 and repeating this feat twice more at Namur in Belgium in 1956 and Brands Hatch in 1957. A British Championship winning spree was also started in 1955 with Jeff winning his first title on the Goldie, this was repeated in 1956, 1960, 1961 and 1962 guaranteeing legendary status before capturing his World titles in 1964 and 1965.

What’s it like mister?

I was more than interested to find out what it was like to ride this Jeff Smith replica DB Gold Star with his familiar No 4 plate. Our test track at Owslebury in Hampshire gave us plenty of scope to test, with hills, cambers, tight and fast bends with jumps, some of which were certainly not to the Goldie’s liking. The bike had been built to original spec, as much as possible but having two way damping in the front forks and a Triumph clutch, and the swinging arm had been strengthened as per period. It would appear a Clubman head is fitted but with Walter Scott winning a 500cc Scottish Championship with a modified Clubman Gold Star there is no doubt all sorts of combinations were used at the time and only Jeff Smith could tell us what he used that year.

The first impression is how low the bike is to the ground, with the front end making the rider feel over the top of it. Once off the start this was no shot in the pants experience but a good old, petrol burning, thumper ride. No quick shifting required as it pulled from nothing in a relatively high gear allowing the rider time to concentrate on course management.

As soon as I started riding I got this image of burly John Burton riding his Gold Star in the old television races. All of us who had the luck, or misfortune depending on your point of view, of riding the muddy winter events knew how a big man on a big motorcycle weighing well over 300lb with a long stroke of 88mm would find grip in the most extreme conditions but to stay competitive with lightweights is another story.

No mud for me on this test though and, pulling high gears, I surprisingly found, on one of the adverse uphill sweeping bends, this bike became the best steering of all makes tested on the day. After all Nicholson’s cutting and altering produced the Goldie we know and the Swedes' Goldie rampage of the 1955 Motocross de Nations is it little wonder the Monark, Lito and Husqvarna used Gold Star steering geometry. Remember it was not just the Swedes who made lighter versions of the Gold Star but the Rickman brothers with their Metisse frames and Eric Cheney with his variations, low footrest position and a low centre of gravity from engine and gearbox made for a great bike to sit on and steer.

Tracks of the era were made for more sitting than standing as were the forward mounted footrests, so not the most natural of bikes to stand up on over bumps but this is only because we have become accustomed to the footrests being in a further back position today. Typically the BSA gearbox felt bulletproof as had the whole bike of the period and this strength and reliability is one of the reasons why Gold Stars were so popular.

The back end was pretty stock, rather than having fancy new suspension units, and coped with the bumps a scrambler would expect to find in the 50s and 60s. At least as far as I remember it as the only Goldie I raced was the late Les Shirlaw’s 350 model. But the more I rode this bike the memories began to stir and that feeling, good or bad, that every make of bike gives becomes more clear, making the Goldie a pleasant experience to be on once more.

Jeff Smith was a more successful man than myself, both with results and mechanical knowledge of four-strokes and when he spoke of the Goldie engine being a freer engine to ride than the B50 it was difficult for me to grasp. After having competed on a methanol burning 500cc B44 Cheney and a Gold Star running on petrol I appreciate the feeling. Strong ponies low down the range make a joy to ride and this bike had it by the bucket loads. No instant wheelies by a snap of the throttle here but jumping was predictable if precise when throwing so much weight about.

I am sure the John Draper Gold Star that won the European Championship in 1955 would have been a faster model than this but am certain that the weight and suspension would not have been much different. How could a man of Draper’s small stature ride to such dizzy heights? Easy, all-round ability. Skill can be acquired but only a few reach a peak of perfection. I am glad I missed racing these men on the track at their most dominant but those who witnessed it, can think themselves lucky indeed. ![]()