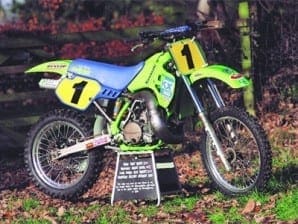

There’s no question that the motocross scene took on a new urgency once the Japanese factories got their heads down and decided to win. With seemingly unlimited budgets the Big Four stormed across the sport and upped everyone’s game. Naturally there had always been factory teams but until BSA started playing around with stuff like titanium for frames they were a bit more low key. By 1988, when Kurt Nicoll – son of former BSA factory rider Dave Nicoll – was campaigning this works Kawasaki, the tide was turning back again and the era of works specials was on the wane.

According to Dave King, the owner of this particular Kawasaki, though Japanese factories had budgets that made the British and European efforts seem a joke not all factories had the same level of finance available.

Slow down in budget

Further evidence of the slow down in budget spending in the paddock would be that Kurt Nicoll was the only factory rider for Kawasaki in 1988 and this bike is one of two built that season. Even though the Kawasaki team had less of a budget to work with, than say Honda, they still managed to put together a fairly special machine and it’s obvious as I chat with him that Dave King is smitten by the subject of such machines and he makes an interesting comment about the late 80s being the end of the works special. In his front room and with a cup of coffee provided by him, I didn’t like to dispute this and made a note to check it later, feeling sure he would be wrong. I should have known better than to question his comment as the research – not exhaustive I admit, but reasonably comprehensive – showed it to be true. Yes, there were specials for favoured riders but in the main they were re-worked production machines.

At the risk of annoying Kawasaki aficionados I’m going to add a personal observation of my own in here and say that like Nicoll, Kawasaki were the perpetual runners-up in the 500 GP scene of that time. This in no way reflects the quality or excellence of the bikes but is more an indication on the way the cut and thrust world of off-road racing works. The bikes should have won, were good enough to win and – in Nicoll, Brad Lackey and Dave Thorpe to name three – had riders capable of winning but it just didn’t happen for them on the GP circuit. Which is more than a shame.

Production range

However, we’re concentrating on the bike here and though hand built it shares features with the production range. Like the showroom models it is water cooled – Kawasaki had phased in liquid cooling in the early 80s starting with the 125 works machine and the factory riders on the 500cc models got a water jacket for the ’83 season.

This extra length is gained in the hand-made alloy swinging arm which also carries the works-type suspension system though an Ohlin damper is used. Up at the front are conventional Kayaba forks which Dave says are the best ones Kawasaki ever used, stating that the later works bikes were fitted with the then new USD – Up Side Down – forks and were plagued with handling problems. While these forks would look standard and may have started out standard, they would most likely have been matched to Nicoll’s exact requirements. Mounting the forks in the frame was taken care of by a standard bottom yoke and a magnesium top one. Kawasaki cast up special wheel hubs in magnesium to save weight but, just in case you thought everything on a factory bike was perfect, it turns out the rear one had bearing location problems. At one stage Nicoll and his mechanic – brother Arran – had to hammer out the trick wheel and slot in a production one which it still wears… canny Mr King also has the magnesium one in storage.

Subject of magnesium

On the subject of magnesium, some of the engine cases are cast from the material and it can save a great deal of weight. There are some trick titanium fasteners too, another weight-saving measure but the company were careful not to go overboard with carving weight off as there was a minimum weight to be attained. Weight reduction had been seen as the Holy Grail for performance and in the days of big British bikes a lot of weight could be safely removed giving an increase in performance without tuning the engines beyond their safe limits. By the 80s though, weight reduction could weaken already light machines and the question of power was irrelevant as two-strokes now produced as much, if not more than the four-strokes had been able to. More importantly it was from an inherently lighter power unit and it was reliable power too. To prevent ultra-light and flimsy machines being produced a minimum weight limit was set and the Kawasaki would be close to it.

Dave admits that he isn’t exactly sure what is inside the engine a nd quickly rhymes off what he does know. “The crank, con-rod and piston will be special components,” he says, “and I know that the five-speed gearbox has very close ratios with hand cut gears.” He goes on to say the clutch runs in oil, the primary drive is by gears and gives a compact engine unit. “It’s fired by an electronic ignition system and there’s only one spark plug,” he grins, adding “you’re making me think a bit.” On a two-stroke the exhaust system is more than just a way to blast the used gases out of the engine and into the following rider’s face, it can make or break the power. Get it wrong and the bike will neither pull, nor rev or be too peaky for use. Nicoll’s bike has his favourite Pro-Circuit pipe on. Tyres are another area that can be a minefield and the wrong choice here will easily see the rider loose a place or two. Nicoll used Dunlops and this was the last year for the 21in front and 18in rear combination as the new era of 17in rear wheels was about to come in.

As Dave racked his brains for more information, he mentally ticked off what he’s told me about the bike. “What about the handle bars and their controls?” I asked. “Ah yes, the bars, they’re a special bend to suit Kurt and the throttle is a special item but the controls are production and I think the cables are Venhill,” says Mr King. “Another peculiarity of Nicoll was his preference for Serval Marketing’s ‘mushroom’ handlebar grips,” he adds. ![]()