Though still fielding machines based on production bikes, the UK team for 1966 had some good kit.

Words: Tim Britton Pics: Nick Haskell

To perform well on the world stage was always the aim of the UK’s motorcycle industry throughout its existence and the International Six Days Trial was tailor made for this purpose.

When it was launched in 1913 the idea behind the event was to showcase what ordinary, or lightly modified machines could do and as such our home industry embraced it.

Gradually though, the focus of the two-wheeled world changed and motorcycles became leisure vehicles rather than transport, but the UK industry soldiered on with lightly modified road bikes for the national teams.

Or at least they did until the mid-Sixties when things had to change. In effect the home industry was BSA Triumph and it was their supported riders who made up the teams.

Good though these riders were, they were often handicapped by their machinery, but they still put up excellent performances.

The thing is, within the industry existed the wherewithal to create machines that could perform well, Jeff Smith for instance was still at the top of the world and for 1966 he was the reigning world champion on a BSA Victor and Triumph’s unit twin engine could easily slot into this chassis, as John Giles proved.

Why didn’t the team consist of bikes built to this ideal? Company politics is why. BSA was not keen to see its chassis fitted with a Triumph engine nor was Triumph all that happy about the suggestion its bikes were inferior to BSA.

The point was both makes were under the same ownership and surely that was the main thing? Hmmm well… As each factory continued to try and scupper the project it seemed common sense had gone out of the window.

One of the biggest bugbears for the BSA guys was the weight of the Triumph engines and that the cast iron barrels on them would distort under hard use. Triumph was adamant that the barrels couldn’t be cast in alloy.

In scenes worthy of a spy movie, BSA called Triumph’s bluff when it cast alloy cylinder blocks for the unit twin engines after Meriden said it couldn’t be done.

Then half the blocks vanished between the two factories. Triumph countered by presenting the ACU with fully refurbished machines from the previous year’s ISDT at the secret test day when BSA had claimed there wasn’t time to rebuild its bikes.

The situation was becoming farcical and a threat by the ACU to hand the whole issue of team bikes to Greeves seemed to make each party grudgingly see sense. While neither side seemed happy, the project did move forward with BSA producing three hybrid Victor-framed machines with Triumph engines – they’d promised nine – and Triumph supplied the rest of the machines from the previous year’s team bikes.

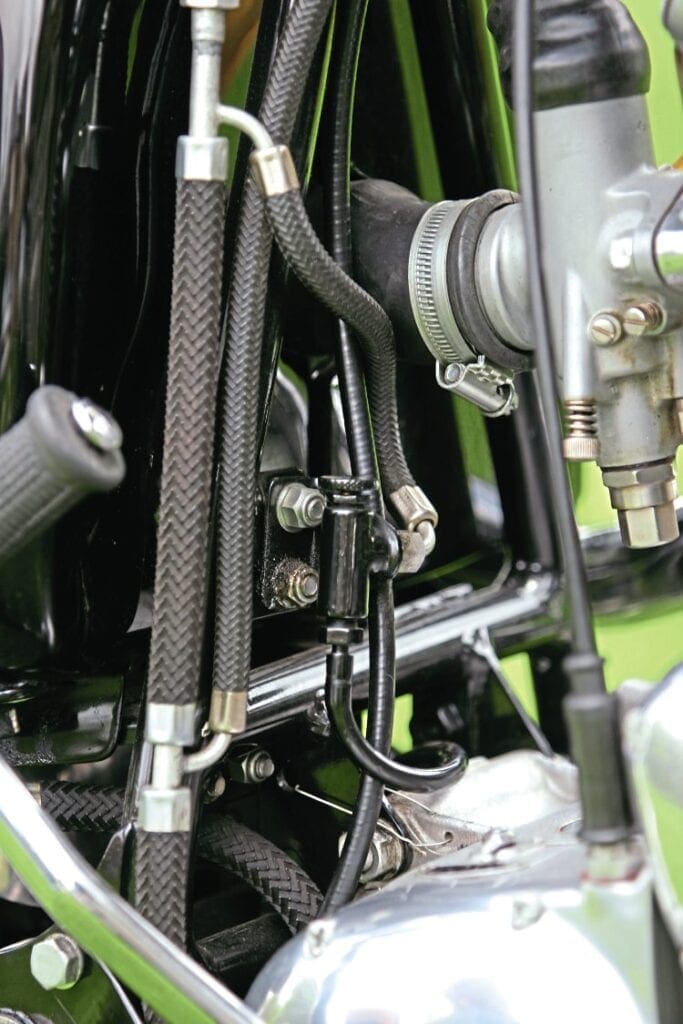

On the face of it slotting a unit twin engine into a Victor frame isn’t difficult but there are issues of chain length to sort out, as depending on whether the dampers were compressed or extended, the chain was either way too slack or bowstring tight.

With time being tight these issues were resolved and the three TriBSAs that were built performed well and the one in our pictures here was ridden by Arthur Lampkin.

It is surprisingly non-trick really, being the off-the-shelf Victor scrambles frame fitted with a Triumph swinging arm and its qd rear wheel.

Up at the front end are Victor forks and a front wheel with the single sided brake that has the adjustable fulcrum slot so the brake shoes can be centralised.

A Gold Star pattern alloy fuel tank, alloy front mudguard and stainless steel rear guard – for strength – and scrambles-style seat complete the ensemble for the chassis.

Engine wise, as well as alloy cylinder blocks, the rest of the internals were to Triumph’s Daytona specification, providing performance and power aplenty.

In order that the generator could be checked without pulling off the whole primary case there was a window cut in it and a cover screwed on.

A massive breather pipe was fitted to the primary case and vented to the rear of the bike it allows pressure to escape and not force oil out of the engine. In recognition of the possibility of a rider having to navigate past fallen competitors or through some serious nadgery terrain, the bottom gear was lowered to give the clutch an easier time.

As per BSA’s desire, the exhaust system was high level on the left hand side to prevent it being damaged, though Triumph team riders preferred a low level system, which kept the very hot exhaust away from the carburettor should anything need to be attended to.

Providing power to the engine was by a 12v Zener diode system for the hybrid bikes, whereas the all-Triumph versions had the energy transfer system it preferred.

In either case the electrics were under each machine’s seat and protected from the weather, event conditions and vibration in their own rubber mounted tray. In a display of even more company politics, those Triumphs to be ridden by BSA men had Victor front ends fitted and BSA on the tank.

Did it all help?

The Swedish ISDT wasn’t reckoned to be all that tough an event – at least to international off-road stars at the top of their game – and had it not been for penalties incurred checking in early for a couple of team men, the UK squad may well have won, but as it was their second place was the best result for a number of years and wouldn’t be matched until the 1973 event in the USA.

Britain in the ISDT

Great Britain has quite a successful record in the ISDT, with 16 wins in the Trophy class or at least in the period covered by this magazine. There have been some very close second places too and additionally the UK teams adhered to the spirit of the competition – using lightly modified road machines – for far longer than other teams. Coincidentally, the UK has hosted the event 16 times during the same period too, though the wins and our hosting don’t match… The UK were involved in probably two of the most famous ISDT escapades, the first being the epic dash from Austria on the eve of the Second World War, the second being using three almost standard BSA 500cc twin A7s to win gold medals in 1952.

Company politics

Though technically part of the same company since the early Fifties, when Triumph was sold to BSA, there were intense rivalries between the two factories. Their team riders may have enjoyed friendly interaction with each other on a personal basis, but a distinct ‘them and us’ was the feeling further up the scale. John Giles fell foul of this attitude when he dared slot his Triumph engine into a BSA frame and race it in a scramble. Triumph boss Edward Turner was less than pleased so Giles was cast into the wilderness for a year as punishment. Ironic really, when the factories had had their hand forced to try just such a combination officially.

Read more News and Features online at www.classicdirtbike.com and in the latest issue of Classic Dirt Bike – on sale now!