When Triumph’s twin engine needed a better chassis for ISDT use, eyes turned to Hampshire and Eric Cheney’s workshop.

On the face of it Triumph’s twin, designed in the 1930s, ought not to have still been at the forefront of competition 30 years later, but it was.

There are a number of reasons for this, firstly it’s a great engine, flexible, easily maintained and actually very reliable, plus it has a range of parts and accessories associated with it which can make it perform extremely well.

Unlike a traditional four-stroke single the twin is a shorter engine with its weight lower down and it is easier to start too.

The chassis they were slotted into wasn’t always the best as they were connected by a lot of bolts and studs and could flex or twist, plus Triumph stuck to the brazed and lugged construction method for a long time.

This meant the frame was generally quite heavy and in the scrambles world riders often wrapped the engine in a BSA frame, usually an all-welded Goldie one which was a stiffer construction.

Once unit construction arrived, the combined Triumph engine and gearbox was slightly smaller than the separate ones and looked lost in the Goldie frame.

The factory team riders carried on using Triumph’s own frame mainly because they’d have little option, though John Giles did slip his works Triumph engine into another frame and got a row for his trouble.

In the main, though, when national team duty called, the Triumph lads were on all-Triumph Triumphs.

Generally speaking the riders did quite well on such machines and they upheld national honour, but as the Sixties moved on they were increasingly competing against small capacity two-strokes and in order to keep up they were riding the wheels off the standard product. It is a testament to their skills that they could succeed but something needed to be done.

Enter the specialist frame makers such as Eric Cheney. Having altered motorcycle chassis for some time, Cheney moved into making complete frames then added his own wheels, forks and tanks, so effectively he was supplying a complete motorcycle minus the engine.

When the British industry pulled out of international competition, a dealer collective got together and commissioned bikes from Cheney for the ISDT.

Ken Heanes – Triumph dealer, former top ISDT star and super enthusiast – prepped engines, Cheney sorted the chassis and legends were created. We defy anyone to claim the Cheney Triumphs are not beautiful motorcycles.

By the time the original Cheney Triumphs were being used, the team had cottoned on to the idea of using an over-bored 500cc engine for the 750cc class.

There are several advantages to this, firstly the resultant bike is considerably lighter than a 650cc machine, secondly the number of spare parts needed for service teams is cut down.

Once on active service the Cheneys certainly proved their worth and allowed the UK teams to carry on riding home products for a while longer.

It is possible they even inspired the attempts by BSA/Triumph themselves with the Adventurer based machines of a couple of years later.

Ultimately though the Cheneys were too late to make a real difference to UK’s ISDT/E record. But as is the way of these things people wanted them for road use as they handled well, and looked good.

Eric was more than happy to provide such frame kits to anyone who wanted to bolt one together and while hesitating to call this a production run there are frames about and even new frames built to old spec which is where the bike in this feature comes in.

Being old, as is the editor, has a few advantages – yes, yes, you ache but can’t recall just why – it also means you’ve been around a while and built up a network of friends, mates and acquaintances in motorcycling.

One such mate, Neil Gibson, has taken to living in the Isle of Man and got involved with the motorcycle display team known as the Purple Helmets who are many things to many people but most definitely motorcycle enthusiasts.

Neil sent a pic of this Triumph and asked “what d’you think?” Silly question to ask a Triumph enthusiast really but he added “my mate is going to ride it in the Retro ISDE later this year.”

It seems the lad, Jason MacNee – a regular off-road competitor – casually wondered what it might be like to ride such a machine in the ISDT/E and the owner Dave Pearce said why not enter the retro version and see. So, as this is being written that’s what he’s doing.

But I’m galloping ahead… Once we heard of this crazy feat we needed to know more so phoned Dave who gave us the scoop on the bike.

The tale starts when Dave bought a 500 Triumph about 10 years ago and rode it for a bit before mentioning to a friend he really fancied one of the Cheneys he’d seen while helping out at the three Manx ISDTs – see our Manx Decade in issue 35.

The friend said he’d build Dave one and the project was on.

It’s also the reason this feature is a bit light on build detail as Dave told me he just handed the whole project over to his friend.

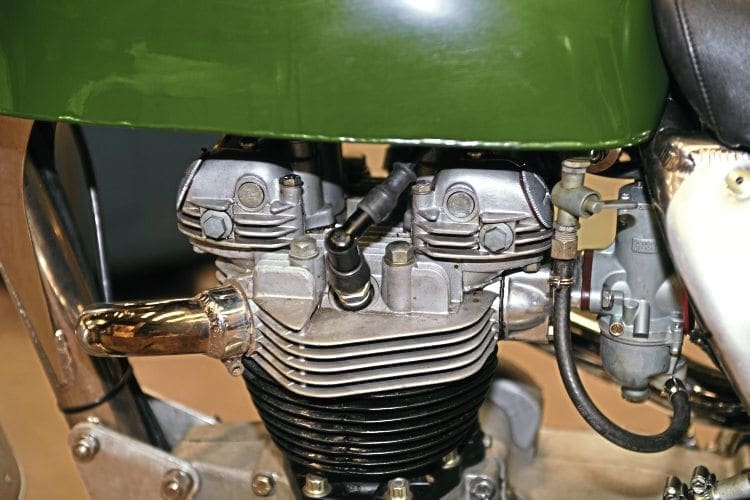

The basis of the bike is an ex-police 650 Triumph which was typically the sort of spec the factory used for off-road engines.

It has the race camshafts but low compression pistons which provides stump-pulling torque as well as a fair turn of speed and acceleration when wound on.

The rest of the bike is pretty much typically Cheney and has an all-welded oil-bearing frame made from Reynolds 531 tube, Ceriani front forks, Triumph rear wheel and a superb Gold Star style petrol tank painted green here but bronze in the day.

The siamesed exhaust system tucks up out of harm’s way yet doesn’t prevent essential maintenance to be done. In short, the concept of success in the ISDT/E had been thought about and the machine produced to encourage it.

In the day

The 1971 ISDT team included a lot of the established off-road stars of the day including Mick Andrews and Mick Wilkinson who have both, independently, told CDB what these machines were like. Mick ‘Wilkie’ recalls his being able to top 100mph on enduro gearing while Mick Andrews cites how flexible the power was. It was clear that both riders have a soft spot for the bikes.

Eric Cheney

So often in the history of British motorcycle sport the honour of the country has been upheld by those working on the edge of the industry; those who produced machines which passed into legend.

Such a person was Eric Cheney who, when he found the products of the major factories to be wanting, set-to and made his own machines for the off-road world.

A talented MXer, partnered with Les Archer in the European championships in the 1950s, Cheney’s own top line race career came to an end when a prolonged recovery from an illness (thanks to a bug picked up competing abroad), kept him away from the GP scene.

Always keen on making his own machinery Cheney turned his talents exclusively to producing motorcycles for others and some of the most iconic competition machines of all time emerged from the Hampshire workshops of Cheney Racing.