The ISDT often showcased future developments in our industry and proved they would work too. Naturally the press were there.

Words: Tim Britton Pics: Mortons Archive

This is a little bit of personal indulgence on my part here… and I suppose I ought to apologise for that…. but it’s probably obvious to regular readers that the archive here at CDB is an extensive place, and not a little dangerous.

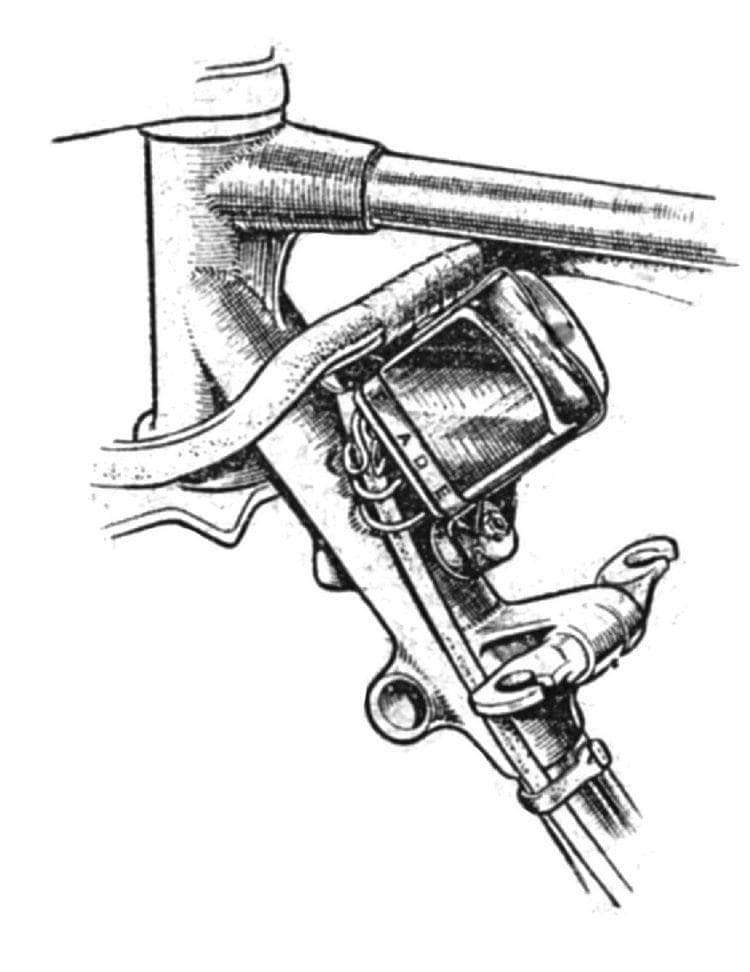

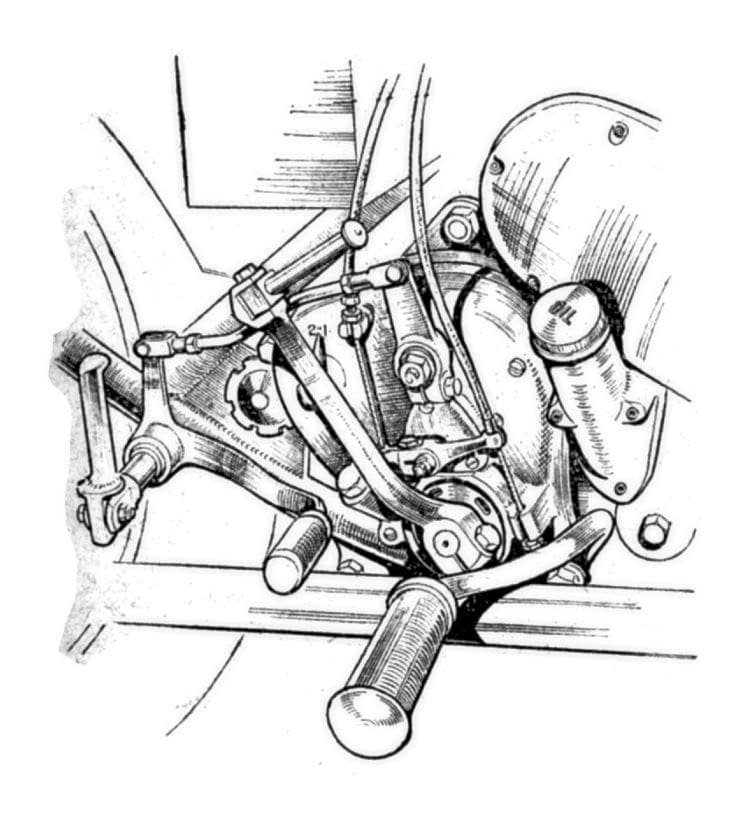

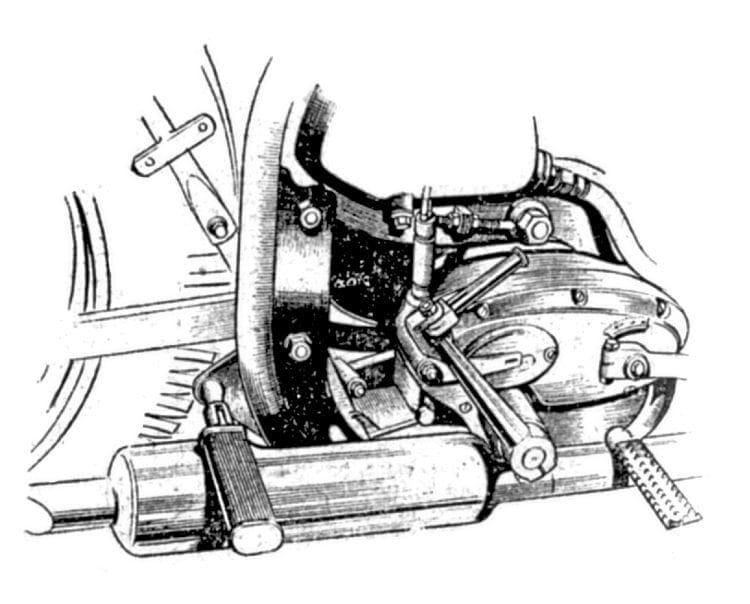

‘Dangerous’ because of the content and the subtle way time vanishes – you see, I’m a sucker for the line drawings produced by the likes of Lawrie Watts in The MotorCycle and MotorCycling in the days before computers when technical artists had to sit down at a drawing board and produce images from sketches they’d made and notes they’d taken in the most oddball of circumstances.

These line drawings have a section all of their own within our normal archive where the original images are stored in art folders. The danger comes when looking for the drawings in a feature such as this 1952 ISDT test. It is so easy to become distracted… which is why the archive feature for this issue is a little older than we’d normally go.

You see I was looking for something else and the cross reference threw up the ACU organised test of potential team members for the 1952 ISDT.

Once the drawings were laid out several had date references, so it was an easy job to find the MotorCycle edition they’d been used in and cross reference it to the MotorCycling back issues.

To digress slightly, the basis of the archive is the back issues, images, glass plates, machine files and brochures used in The MotorCycle since 1902.

There are some MotorCycling images too, but due to a storage disaster many years ago involving damp, most of the MotorCycling stuff was turned to mulch whereas the MotorCycle material was stored higher up and survived.

Luckily we have the back issues and a repro department which can work wonders…

Anyway, looking for the feature inspired by the drawings soon brought to light that the 1952 ISDT in Austria was set to be an interesting one for a number of reasons, and as winner of the International Trophy contest for the previous four years great things were expected of the British teams.

The event would turn out to be a much tougher one than expected and the UK teams were not the only ones who suffered mechanical failures, accidents and organisational disasters.

The weather and atrocious conditions put those on larger machines at a disadvantage as their power could not be used to make up for lost time.

For UK team riders who did manage to negotiate certain extreme sections of the course and maintain some semblance of time they found these sections would be scrubbed as many other riders didn’t make it. Normally reliable machines such as the factory Triumph twins suffered gearbox problems… and the list went on.

There was some silver lining though, as the 1952 ISDT was the one where three standard BSA A7s were used as a club team and all three won gold medals and lifted the Maudes Trophy for BSA.

However, all the problems, heartache and misery was still in the future and as the ACU organised the ISDT selection tests in Llandrindod Wells in Wales in July things looked promising.

With the major manufacturers represented, their star riders on hand and the gentlemen of the press to record it all, the selection tests could begin.

These tests were to find out the suitability of the machines plus the ability of their riders to cope with the expected conditions in Austria later in the year.

It was also a chance for the manufacturers to trial a few developments in similar conditions to an actual event as Llandrindod Wells had hosted the ISDT several times.

With riders and machines arriving in the Welsh town throughout the day journalist and artist were kept busy photographing and sketching catching up on the latest developments.

I suspect they would have been made aware by the factory publicity machine of each maker’s new developments and would be seeking them out to see for themselves.

With the major manufacturers all having many years of experience in such events, the interesting differences were to be found in the detail.

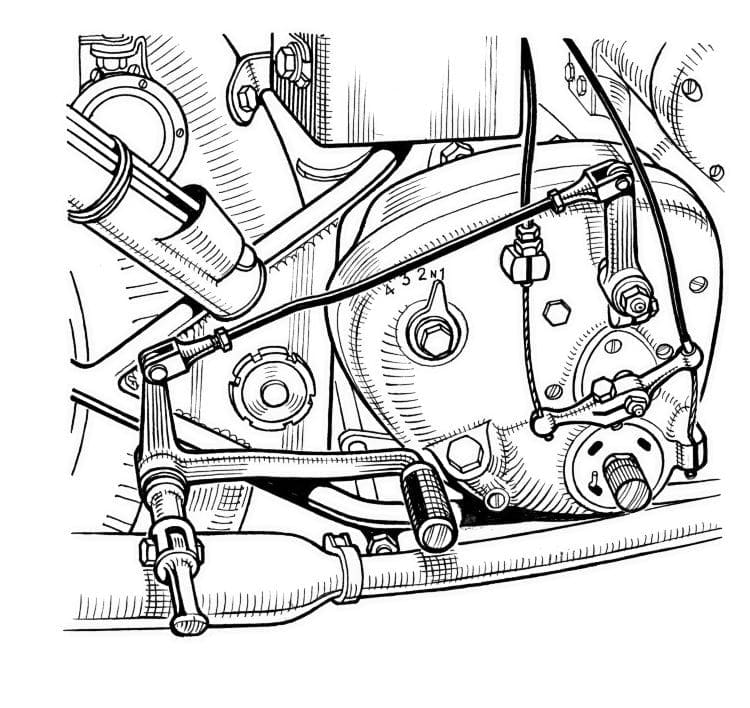

Common features included Tommy bars welded on to the spindles of wheels already of the qd type, spare carburettor slides secured in tubes ready to fit, spare cables running alongside the originals so changing one would be the work of seconds and, in those days of rigid footrests, a spare one secured to the frame.

All pretty much common through the different marques.

Where the interesting bits started were when makers launched either completely new machines or radically altered older ones. Take Ariel for instance.

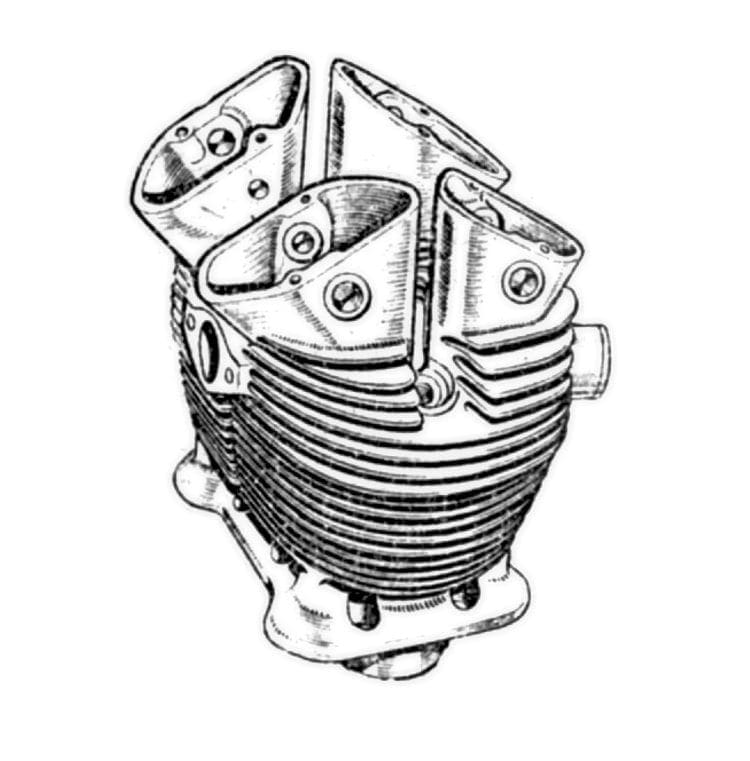

Though a 500cc twin had been in its range for some time, the ones presented at the selection tests featured an all alloy engine which was claimed to be designed especially for the ISDT.

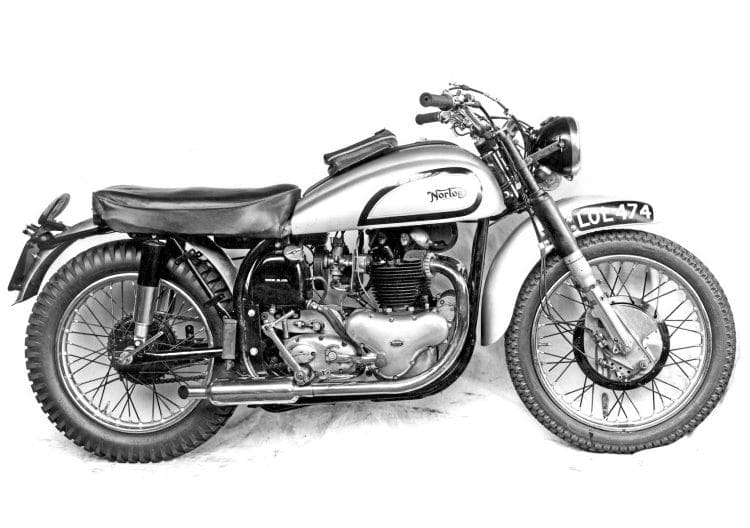

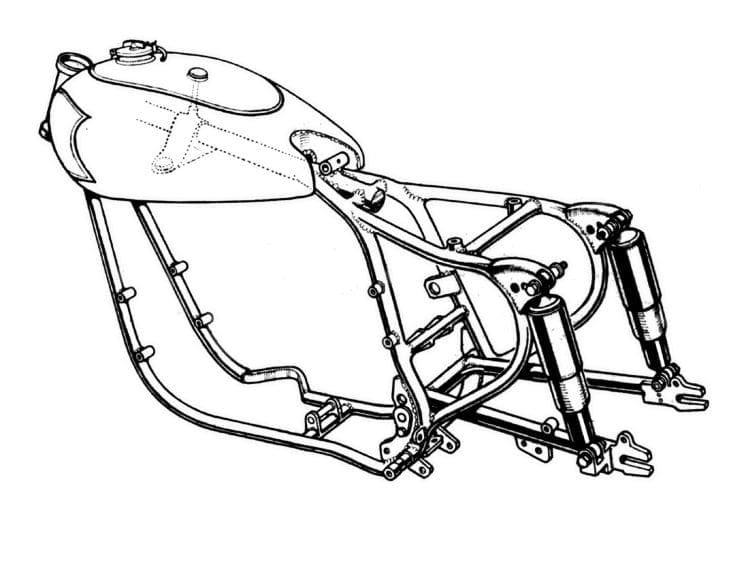

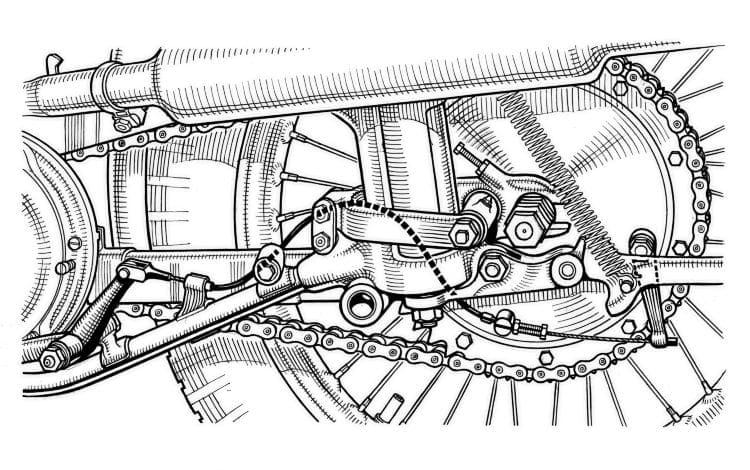

BSA too turned up with a new frame for its single cylinder 500s. Claimed to be the road racing frame, it was of the swinging arm type and featured a single point tank fixing mount and would form the basis for all future scrambles frames.

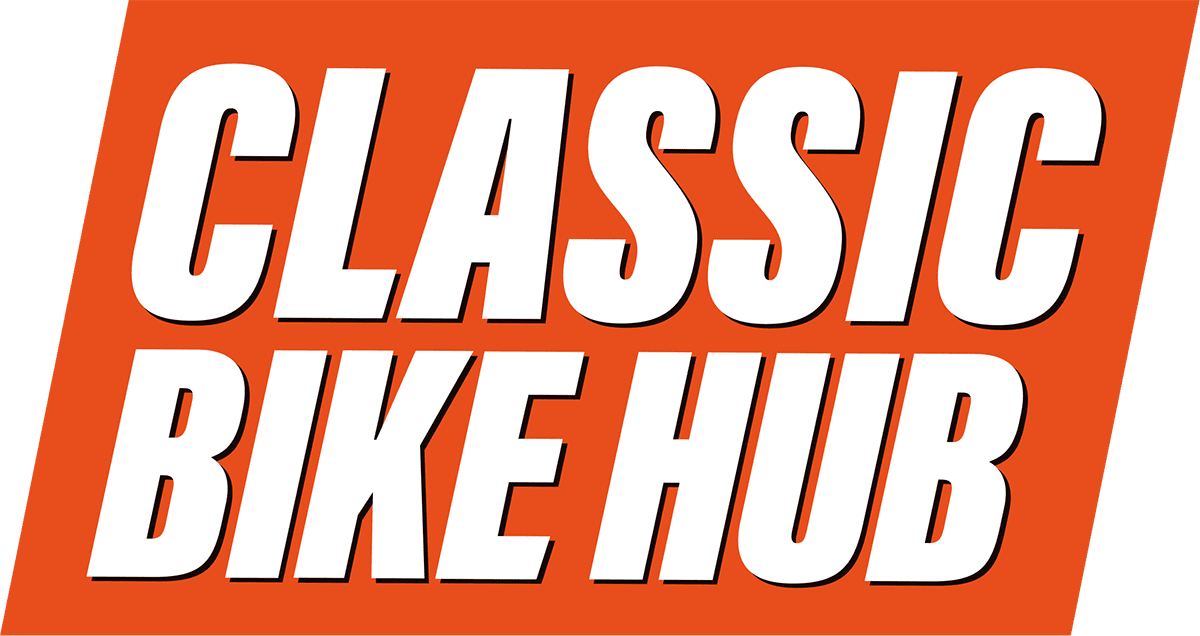

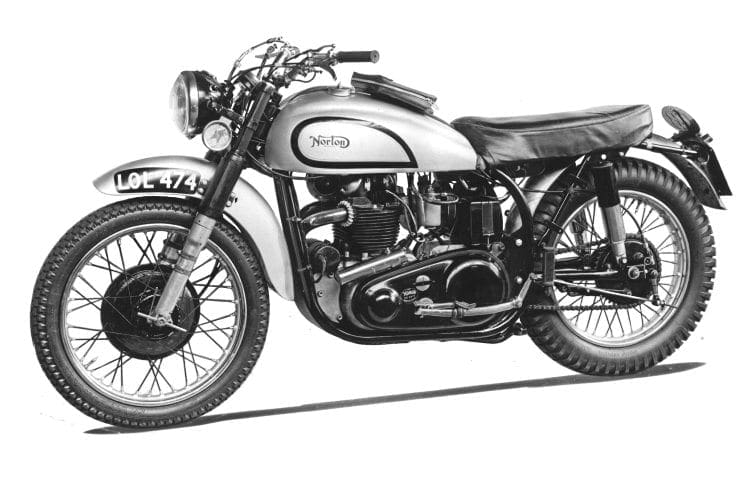

Norton and Triumph placed their faith in machines almost as they were the year before, with the Meriden twins not even having rear suspension – it being difficult to produce a qd wheel for the sprung hub.

With a nod to the future the ACU had specifically requested those manufacturers who produced small two-strokes to come to the tests. This was with the realisation that European makers of small bikes often had the advantage of more forgiving speed schedules and section times in the ISDT.

In the end it was Francis-Barnett which stepped up to the mark and brought three machines along for the test and also one of the company founder’s sons came along too.

A testing time

While the machines themselves were to be thrashed as hard as they could be over the two days, with a morning and afternoon lap of around 115 miles plus a speed test and a night run, all of which would feature in the ISDT, the riders too would be tested to see how quickly they could accomplish maintenance tasks and simple repairs.

During the running of the test it was likely a rider could be halted and asked to do any number of mechanical jobs from changing a tyre to removing the float in the carburettor, or swapping cables and points – all of which were designed to replicate problems which could be encountered on the route.

Such tasks would present little problem to factory riders and they would likely have been practising the fastest way to do just these things.

Also showing a fair turn of speed were three riders in the speed test, one of the requirements of the ISDT then was to maintain an hour at a constant speed – let’s say 60mph – which ended up with riders going faster and faster until the inevitable spills… youthful exuberance isn’t a new thing…

In the end the tests were certainly of value and each maker went away with food for thought and not a small amount of wreckage to consider before the September event.

The riders themselves were chosen from the finest of the off-road world. Representing their country in the prestigious International Trophy contest were Hugh Viney, Jim Alves, Bob Manns, Jack Stocker and Bob Ray. The Vase A and B teams were to be Dick Clayton, Stan Evans and Ted Usher and Johnny Brittain, David Tye and Rex Young.

A quick quartet

A couple of weeks after the selection tests MotorCycling’s man Denis Hardwicke had the opportunity to test four of the actual machines – Rex Young’s Norton Dominator, Jack Stocker’s 700 Enfield, Bill Parson’s Ariel and David Tye’s Goldie.

Parsons was on the selection test and his bike was exactly as teamster Bob Ray’s Ariel. These four were deemed the most special of the proposed ISDT team bikes as they differed so much from production machines.

Hardwicke hauled out his footing-coat, pulled his beret firmly on to his head and set off to report on four motorcycles designed to take on the toughest competition in the world. Denis got his hands on the Ariel Hunter twin first and the bar was set extremely high.

Though based on the production machine, Ariel had gone to town on the design and execution of this version and it was noticeably the lightest of the four bikes thanks to its alloy barrels and head and a performance increase from careful attention to the engine.

Keeping all this power on the ground was the job of special hydraulic dampers made to resemble the plungers of the standard machine. A further mod was to use a cable rear brake system which kept the brake pedal more constant and allowed more sensitivity. It was with some reluctance Hardwicke returned the twin to Selly Oak but there was a Royal Enfield twin to try next.

On getting the Enfield our man noted it had rear set footrests and foot controls for use by the rider in the speed tests, allowing him to tuck further in behind the steering head for less wind resistance.

It worked too as Denis hurtled along a straight stretch of road, glanced at the speedo which registered 75mph… then snicked into top gear. With the engine still providing power Hardwick reckoned the 95mph showing was still below the maximum available.

This was confirmed later by RE man Charlie Rogers. After further riding that day, Denis reported any rider issued with a machine which could leave a black tyre mark on the road had better have a steady throttle hand. He also reported that visually there was little to distinguish the 700cc model from the 500cc one but it was physically heavier.

Of the four machines he rode Hardwicke felt some affinity with the Dominator Norton, as he had had some experience of the company’s race machines.

On the face of it using road practise for an off-road machine would seem odd, but it worked. The machine promoted complete confidence in the rider.

Hardwicke admitted he was taking liberties with the machine to try and promote some quirkiness but even aiming at potholes and barrelling into corners way too fast then slamming on the anchors failed to faze this excellent twin.

The final one of the four, BSA’s Gold Star, had an incredible amount of power available and was wrapped in the latest swinging arm frame so it handled well and according to its rider David Tye “would almost steer in mid-air.”

Being developed from the scrambles frame the chassis would have little bother in coping with the rough terrain and Hardwicke was impressed with its sure-footedness whatever the surface, and it was another machine he reluctantly returned to the factory.

At the end of the day though history would record it was the three Star Twins ridden by Vanhouse, Rist and Martin which would bring the honours to the UK and BSA, but that doesn’t devalue the selection tests, nor the lessons learnt from them and, despite the hiccup in 1952, GB would lift the International Trophy again the following year. So yes, the lessons must have been learnt well.

Part of the club

Both of the then-top magazines took a slightly different approach to reporting the feature in that MotorCycle featured the teams and machines in one three page report, while MotorCycling had four pages in one issue and followed it up with a spread test of four team machines. To put that last bit in perspective, imagine being invited to an F1 pre-season test to watch what went on then be allowed to take away a Mercedes, Williams, McLaren and a Ferrari to try them out yourself…

Accessories

There were a number of accessory manufacturers present at the test too, from oil suppliers to helmet makers, and the ACU announced that each rider would be wearing a racing type helmet – though didn’t say who would supply them – and each rider would have a Barbour suit, while their tyres would be protected by Dunlop’s puncture sealing compound. In those far off days, plastering your machine with stickers and badges was not only frowned upon but banned under ACU regulation. Suppliers could crow about it in the press but not advertise such products on their machines until well into the Sixties.

Dissatisfied from the Midlands

The ISDT was originally intended to be the shop window for production machines and by and large the British industry had played fair on this.

Yes there were the ‘on the day’ modifications to speed up maintenance work during the event – things such as Tommy bars for wheel removal, competition tyres and slightly different handlebars were seen as acceptable to the buying public.

However, there were growing grumbles from the ordinary enthusiast at the sometimes radically different machines used by the teams while successes being touted as ‘same as you can buy’.

Clearly this was not the case and certain things were highlighted by more than one reader to the point where editorial space was devoted to some semblance of explanation.

One point raised was the spare cables taped in place on ISDT machines and the grumble was if a cable couldn’t last 1000 miles then surely the design was wrong.

This was easily explained by the higher chance of accident damage in an event like the ISDT.

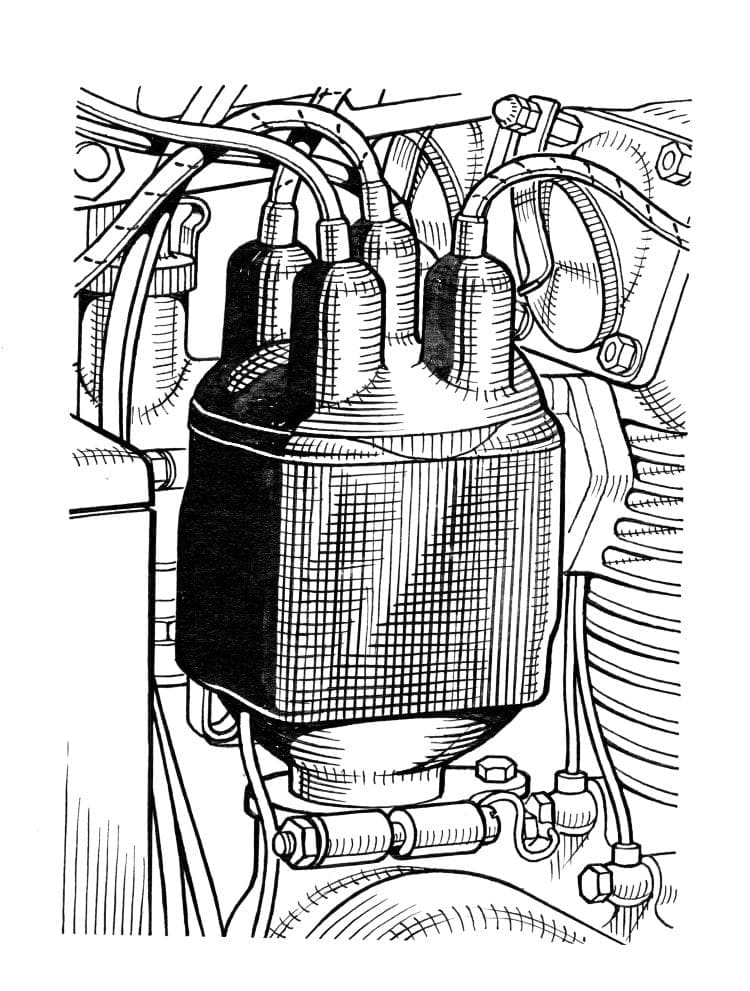

Less easy to explain away were things such as alloy barrels and heads where production machines wore iron cable instead of rod operated rear brakes, air scoops on brake plates and better weather protection for electrics.

Surely, complained readers, if these mods were better they should be incorporated in production models. The sentiment wasn’t hard to understand but missed the point that the ISDT had become less of a shop window for machines and more of a way to gain national prestige.

Read more News and Features online at www.classicdirtbike.com and in the latest issue of Classic Dirt Bike – on sale now