We’re all nosey aren’t we? We all like to see what the other fella’s bike is like to ride. Doesn’t matter if it’s our riding buddy who we share lifts with or the top line bike that wins each week we’re curious about it. Would it suit me? Am I missing something that would work on my bike? Is it easier to ride than mine?

There’s a load of other questions too but you probably know them and don’t need me to list them. Like me though maybe you’ve some preconceived notions about bikes that are successful and how far up the list we’d go if we rode them. The problem with preconceived notions is they are more often wrong than right. It’s a fair bet that what suits one rider doesn’t always suit another as things like ability, confidence and physical dimensions all play a part in the package.

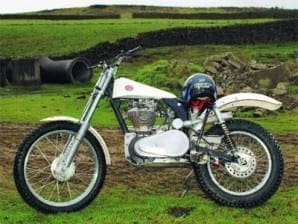

Take this Ariel for instance, that it’s a winning bike is not under question as its owner and builder, Neil Gaunt, has just won the Classic British Experts on it and also the Pre-65 Scottish Two Day Trial a while back so naturally it must be good to ride. Just how good it is, CDB got the chance to find out one grey day in January.

Organising a photoshoot in the middle of winter is always going to be a chancy business and there were several false starts before we finally got together at one of several secret test locations in the wilds of Yorkshire. While the weather wasn’t perfect, at least it was mainly dry for part of the day and it gave us the chance to have a wobble on a bike with a proven track record. Like Andy Roberton’s bike elsewhere in this issue, there are rumours of the Gaunt bike being an exotic creation, bristling with fancy metals and lightweight unobtanium. Like the Roberton bike, the rumours are wrong. Oh, the bike is far from standard Ariel but then again, few people ride a standard bike in pre-65 trials and having ridden a catalogue HT3 I’d doubt one would do you much good in a quest for the sharp end of the results.

The weather played a major part in our day and altered the way a test is normally conducted, at least for me, as we took advantage of the daylight and did the riding first. First of all, it’s fair to say that Neil is more of a modern rider than a classic rider and the bike reflects this type of style. The bike actually fits me quite well as we’re near enough the same height but, mainly due to a back injury that’s now mended, Neil is a pound or two heavier than me and the suspension is set for him which meant it took quite a bit of time before it warmed up. If this were a cost unlimited test I’d have a selection of springs available for comparison but it isn’t so I just had to ride the bike as it was.

It’s a first kick starter, thanks to a recent return to a PAL electronic magneto that has cured all sorts of flat spots and problems attributed to elsewhere in the package. Under way the controls all felt extremely light to use and I rode round the fell at our test location just to get a feeling for the bike and educate my feet and hands as to where everything was – the last thing you want is to be in a spot of bother with your foot not able to find the brake. For this reason the right foot has an incredible amount of work to do as Neil prefers his rear brake on that side. With Bultaco and Montesa machines it was possible to swap them over thanks to a through shaft in the gearbox but a Burman gearbox has no such luxury and a complicated linkage would be required. Neil just uses everything on the right.

Though there were some useful rocks here and there I elected to try simpler stuff first and did some full-lock turns and figure-of-eights on tickover to see how it behaved and how easy or otherwise it was to control in sections. I found that the Villiers carburettor was just perfect as the bike trickled along on a whisker of throttle then leapt forward when the throttle was opened. There are a number of riders who prefer the Villiers instrument to the Amal reckoning that it works much better and meets the regulations for pre-65 events where a carburettor has to match the country the engine came from.

As I settled in to the feel of the bike I tried some of the rocks and it was interesting to compare the sharper power from the 500 to that of my 350 B40. In the wrong hands – mine for instance – things could very quickly go wrong. I despaired of getting to grips with the bike and was resigned to admitting it didn’t suit me until I called a halt under the pretext of wanting a coffee and watched Neil take it through a series of sections that I’d not even attempt. It was then that I realised what my main problem was, Neil was riding the bike like a modern Montesa and I wasn’t. There was a lot of clutch work going on and he was flicking and pivot turning the Ariel around as if it were a fraction of the weight. Time for another shot I thought, this time with a more modern frame of mind. Not easy, as the last modern trials bike I rode was an air-cooled Yamaha TY Mono and that was in the ’89 Scottish.

OK, let's try some turns around these rocks then, accelerate towards them, weight over the front wheel, dip, pull on the bars and blip the throttle… aha! That’s better, a bit of bounce to help the back end round and we’re almost looking like I know what I’m doing. I’d still have picked up a five if this were a trial as I shot out of the bounds of our practice section the first time. Not the second time though and I started to get the hang of it.

Despite the greasy nature of the rocks it was possible for me to get grip when I tried to ride like Neil, though I didn’t leap up rock steps like he did as I felt I’d need quite a bit more practice for that sort of going. With confidence growing in the bike I tried the stream section and it was here that I felt most in need of softer suspension as the assembled crowd of trials riders pointed out the forks and dampers were barely moving.

Actually, as I’m writing this, a cheering thought has occurred, normally I’m wanting stiffer suspension on bikes I ride because I’m on the heavy side, this is a ‘first’ for a long time anyway, that I’ve been lighter than an owner – sorry Neil but you did mention it. It also highlights the importance of correct spring rates at either end of the bike. So, if you’re slipping and sliding around maybe you ought to be looking at this area.

I suppose I ought to come clean at this end of the test ride and before we nipped back to Neil’s workshop to chat about the building of the Ariel. There is no doubt at all about the success of the Gaunt Ariel but it was at the far end of our test day before I began to click with it and even then it was still a big bike that could easily take charge of me. I’m guessing here, but I’d say most classic riders would feel the same way however, if you’ve hopped off a modern bike and on to Neil’s bike I think you’d be at home straightaway.

I was interested to hear about the way the bike was designed and what determined the dimensions Neil settled on. “The project started with an emulsioned wall,” says Neil. Er… come again.. “We’d just finished the office here at work” – Neil runs a contact earthworks company and has a massive workshop for wagons and plant machinery, with an office for the paperwork – “So, I got hold of Mick Grant’s Ariel, put it up against the wall and marked the positions of the handlebar, swinging arm spindle and wheel spindles on the wall, then put my Montesa against it and found it was to within an inch of each dimension.” He goes on to say Mick Grant has been very helpful throughout the whole project and the engine in the bike is one of two Mick built. “I told him I’d buy it off him, he sold it to me and regretted it ever since, he still says it’s the worst decision he’s made,” laughs Gaunt the Younger. The head is the smallest one that’ll fit and it has a highish compression piston so it’ll rev but not got any really special bits inside. Like Granty’s bike, Neil’s uses a Villiers carburettor and this is the only part that his dad had helped him with. “A lot of people think I’ve had a lot of help from my dad but I’ve done it myself apart from the carburettor. I’m not an engineer,” he says, “but I will work at something until I get it right.”

The actual starting point for the Ariel was a replica frame from Paul Jackson and he just kept adding bits to it. “Basically the chassis hasn’t been modified from that start point, I’ve gusseted the head stock when I found it needed strengthening but apart from that the frame is the same.” Fork yokes come from engineer Alan Whitton and they are dead straight with no off-set. Mounted in the yokes are Betor forks, from a Cagiva trail bike but the bottom end is Norton Roadholder. “The damping is just as Cagiva used,” says Neil, “I didn’t modify them at the build stage as I wanted to get it up and running first, then, when I rode it I found they were just right for me.”

We were running ahead of ourselves here so I got Neil to back track a little to the basic frame with and engine and forks in. Obviously a gearbox is needed and traditionally Ariel used a Burman box as does this one, there’s a road cluster inside. Connecting the engine and gearbox though is a bit special. “I got a Beta clutch and had it built into a belt drive unit. I gave the lad who did it a free hand and was prepared to adjust the gearing on gearbox and rear wheel sprockets.” This turned out to be the case but the sprocket on the Whitton rear hub isn’t huge. “I think it’s just about right now,” says Neil.

Finishing off the rolling chassis is another Whitton hub at the front and alloy rims on either end that wear Michelin tubed tyres. Other makes have been tried in the past but Neil has come back to Michelin. Topping the bike off is a tiny, three litre petrol tank, painted white. Why painted and not polished, it is alloy? “I made it myself and the welding isn’t brilliant, painting tidies it up,” says the man. What else have you used then Neil? “Handlebars are Renthal, just like most people use, the controls are Domino, again, lots of other pre-65 bikes use them and I like them better than the Amal ones,” he says, adding “all the fasteners have been converted to metric but they are stainless steel rather than anything exotic like alloy or titanium. I suppose I could save a fair bit of weight with fancy stuff but there’s other, easier, things to do first.” ![]()