Bikes don’t win events on their own, they have to be ridden and arguably a very good rider can win on a moderate machine but put a good rider on a good bike then great things happen. Except, in the case of this particular Greeves, nearly don’t happen. Yes, that’s right, nearly didn’t happen. “Bloody thing broke down in every trial for nine weeks before the Scottish. I was so sick of it, at one trial I didn’t even take it off the pick-up but climbed up, fired it up while it was still tied on, revved it and it stopped so I went home,” says Bill Wilkinson, winner of the 1969 Scottish Six days Trial. “I even said to my dad that I wasn’t right bothered about going up to Scotland for 1969.

The bike went back to Greeves, they had it all apart and couldn’t find anything wrong with it, I went to Scotland and it never missed a beat all week,” he says, adding, “the only problem I hit was at the top of Laggan Locks when, a couple of feet from the end of the section, the split link came out, somebody even found the link in the rocks. They’d seen it come out and shouted up to me ‘did I want it?’ Imagine that! A split link in those stones at Laggan, you know what that section is like,” he laughs, seemingly still unable to believe it himself, “Other than that, and a couple of tyres, a bit of servicing was all I needed to do.”

Enjoy more Classic Dirt Bike Magazine reading.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Bill told me that they never did get to the bottom of what caused the problems in the events the week before. “They did look and look properly because Greeves would do anything for us lads, they were a great company to ride for. It seemed like nothing was any trouble for them and they would renew bits and pieces when we took the bikes back to the factory.”

He went on to say that if something like the lovely alloy petrol tank had so much as a scrape in it, off it would come and a new one would go on. “The wheel rims were the same, if the comp shop thought they were tatty or scraped they’d simply cut the spokes out and lace on a new rim. Mudguards, bars, levers, all the same, in the bin they’d go and fresh ones on.” The Yorkshireman admitted that just occasionally he and the other works team riders would haul the bits out of the bin and spirit them away when the factory wasn’t looking.

Around the time that Bill’s bike would leave the factory there were some changes brewing in the off-road world, the British industry and Greeves in particular. Like most of the lightweight makers, Greeves relied heavily on Villiers for its engines. This company had been supplying a range of two-stroke units to the trade and public for as long as an industry had existed. Their range of engines did include something for every application of the two-stroke unit – chainsaws, light cars, stationary engines, machine tools as well as motorcycles – unfortunately, they had been absorbed by take-overs and were no longer in charge of their own destiny. Villiers made it known that production of the basic engine units, including those needed by Greeves for the Anglian – initially 32A, latterly 37A units – would cease as troubles in the industry, it’s collapse really, were beginning to be felt.

Luckily for Greeves, demand for their mainstay, the Invacar was declining and they had stocks of the engines on hand so were not to be affected straight away. A company called Metal Profiles had purchased the rights to the 32A and 37A engines as their own subsidiary – DMW – needed them too. At least for a period Metal Profiles were happy to supply other manufacturers. The then UK government also had an unwitting hand in Greeves troubles.

A loophole in the pre VAT Purchase Tax meant any motorcycle supplied in kit form avoided the extra taxation. This was good for many smaller manufacturers but a route that Greeves did not follow, preferring to be loyal to their dealer network by supplying ready built bikes. Ultimately though, it was the end of Villiers engined machines and Greeves own engine development was aimed at MX and road racing with their Challenger. No doubt they could have made a trials engine too but with limited resources they would have been stretched. Instead they looked further afield for a proprietary unit and settled on the 170cc Puch engine.

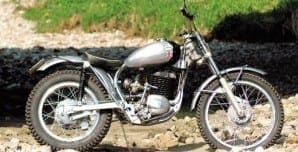

However, this was a year or two away and the familiar Greeves package of beam frame and Villiers engine but with telescopic front forks rather than the leading link ones, was what Bill went to Scotland with. So, were the bikes specially built for the team, I asked? Maybe I was expecting some secrets to come out now 40 years on, tales of hand-built machines fabricated in the toolroom rather than the factory floor, special tuning, titanium bits, magnesium castings and other exotica that us average club riders secretly believe all works bikes have. “Not a bit of it,” says Bill, “they were basically standard bikes, the production range were pretty well sorted by that time and would be just as you could buy in the showroom though we used to do things to them ourselves.

Ah, this is what tuned you into a winner then? “Could be,” he answered, wryly, though it was probably the four hours a day me and our kid practised that was of more help. With my mug of Kettlewell coffee in hand I listened and took notice as Bill pointed out a few differences between his bike and the standard model – Greeves Anglian, according to the catalogue – and there were mighty few of them which shows just how right the Greeves was at that time.

Probably the first thing done to the bike, not just this one but all of Bill’s works machines from Greeves, would be to lengthen the clutch arm. “We didn’t add on too much, just enough to make it a bit lighter and have the cable run a little better,” says Bill. It’s fairly obvious that the telescopic forks are in there, they had been an option for two or three years and all the works team had them. It’s a rash thing in this job to assume things and I’ve been caught out in the past by not asking basic questions because I thought I knew the answer…

Not knowing much about Greeves parts I asked if the Ceriani fork units were slotted into standard yokes. “No, they’re not,” chuckles Wilky, “they’re Ceriani motocross yokes which is why my bike steered and the others didn’t. The standard yokes were too steep and I quietly got a pair of these, slipped them on and never said a dickybird.

The other lads were flopping about all over the place and wondering how I was doing what I did, I didn’t even tell our kid – brother Mick, also a Greeves team member – for months. Jim Sandiford even had special yokes made, they were no good though. Once they twigged what I’d done it was obvious and they all did it.” Bill adds that the only way to tell would be to look directly side on at the bike, if you were familiar with Greeves then it would leap out at you.

As we chatted about his bike, Bill confirmed that the cycle parts are more or less basic Greeves catalogue, saying “the front hub is their own but I think the rear maybe a British Hub Company one, or it might be Greeves copy of one. It looks the same as all the ones previous to it. I put a Villiers air cleaner on it because I thought it was better than the Amal one.” How about the chrome finish on the frame, I asked? Was that just for works machines? “No,” says Bill, “when I took the bike down to the factory, I told Bill Brooker, our team manager, I wanted it chroming like DR’s – Don Smith – bike.

He hummed and hah’d, telling me ‘oh, Bill, don’t know if we’ve got the budget for that, it’s expensive you know,’ I went away thinking, well I tried. Anyway, I went back down later in the week to pick the bike up, Bill says ‘it’s in the paint shop,’ so along there I went. The lads in there just looked at me when I asked where my bike was. ‘Not here,’ they said, I was in a right frame of mind when I went back to the comp shop, I was going to give Brooker a right mouthful for mucking me about. First thing I saw when I went in was my bike, all chromed, it was beautiful. He thought it very funny giving me the run around,” laughs Bill.

Putting his machine troubles behind him, Bill had an excellent week in Scotland and finished on 30 marks to lift the Alexander Trophy – which is still awarded for the premier performance. What happened to the bike after the Scottish I asked? “I bought it from Greeves but sold it straight away, you needed the brass in those days and Greeves got me onto the Pathfinder. I never did get on with it, our kid did though, he thought it were a great bike. I lost track of the bike for a while – 18 years – then it turned up in Huddersfield,” he tells me. “I got Jim Swallow to restore it for me and he’s done a good job on it putting it back to what it was in 69. It’s actually going up to Scotland again, I’m guest of honour at the pre65 this year,” he says. ![]()