FROM OUR ARCHIVES

Though history records Les Archer as being European motocross champion in 1956, results, or lack of, at the start of the season suggested a different outcome for the series.

Words: Tim Britton Pics: Mortons Archive

In an interview with Ralph Venables, published in The MotorCycle in September 1956, Archer admitted his season had started badly, something backed up by the reports of the first three events. Not that these reports were in-depth, as for some reason despite the UK having a reigning European champion in BSA’s John Draper, the 1956 series attracted only minor coverage for the foreign events.

It was left to Venables to tease out the reason for the early season problems which Archer allowed were due to a front brake problem in the first round, a melted spark plug in the second and a crash in the third. Luckily for the ‘Aldershot Flyer’ each of the rounds were won by a different rider, so spreading the points a bit.

It could be hinted that perhaps this wasn’t to be Les’ year but he won in support races at these events, if not with ease, certainly convincingly. This proved he was on the right track and when he lined up for the start of the French GP at Rouen he mastered the wet track and won his first GP of the season.

This was quickly followed by wins in the UK and Belgium and a second in Luxembourg to hoist him to the top of the table. Not only at the top but unable to be beaten and the best that could happen would be a tie with John Draper should the Cheltenham lad win the next two rounds and Archer fail to finish.

Naturally, Les made sure of his title, despite a poor, for him, show in Sweden where he managed only fourth which didn’t affect his total score in the series so far, he won the final round in Denmark to finish on the maximum of 32 points – the scoring being eight points for a win, six for second and so on, with the rider’s best four results to count.

Given how easy it is in 2016 to travel to almost anywhere in the world, certainly anywhere in Europe, the difficulties of foreign travel 60 years ago can be forgotten. These days there is no need to arrange carnets for bikes, or international driving permits and most insurers will have Continental cover written into their policies. So, looked at in this light, the exploits of Archer and his contemporaries are even more remarkable as they travelled from one circuit to another, generally fitting in a visit home too.

Not for these lads the luxury of a motorhome or artic trailer to use as a workshop and to haul their equipment to the next meeting. Even for superstars in those days it would likely be a car and trailer or possibly a pick-up truck but it was not unheard of for top competitors to ride their machines to events.

The road to European success had been an interesting one for Les Archer, not only because he chose to do it as a privateer – albeit one with the contacts of a major motorcycle orientated family business to ease things slightly – but because Archer junior could easily have made road racing his career.

Indeed, in the Venables interview, Archer attributed his success in scrambling to experience gained racing on the road, where a cool head is needed and the ability to react instantly to developing situations is learned. This tarmac stuff notwithstanding, Archer’s first competitive outing was as a 16-year-old in 1946 when he lined up on an ex-WD Matchless at a North Hants club scramble. Leaving the event with the first of what would become many trophies – Best Performance by a rider under 20 – didn’t impress the journalists of the day who dismissed this as ‘okay but the lad has no future as a scrambler’.

Les did seem destined to make his mark in racing as he managed a third in the Lightweight Clubman’s TT of 1947, scored a load of short circuit wins and matched his father’s win in the Hutchinson 100. All seemed good for this aspect of sport but fate was to intervene… Along with most young lads of the 1940s through to the early 60s Les had to complete National Service.

The simple fact it was easier to manage a weekend off to go scramble on a Sunday, than it was to get the Friday, Saturday and Sunday for road racing, shifted his focus from roads to dirt. Once his military service was over, Les realised his road racing experience was outdated so carried on scrambling.

Les also tapped into the Continental scene very early on, telling both Venables in the 1956 interview and Mike Bashford in a 1967 interview, he saw the European race scene as a business, explaining he could earn much more in non-championship races than he could in a GP. This was one of his reasons for not contesting the European championship before 1956, another being he found GPs to be unsettling and reckoned to have had more rows with officials at GPs than any other type of meeting. An exception to this state of affairs was the French GP, an event Archer reckoned to enjoy thanks to the much more friendly atmosphere. His record of four wins there suggests this was the case.

However, despite his professed lack of interest in the European championship before 1956, Archer did contest the odd GP and credits beating Auguste Mingels in the 1955 Luxembourg GP as his catalyst for taking a shot at the title the following year. Mingels was the reigning European champion having dominated the series in 1954 but wasn’t having it all his own way in 1955, as John Draper harried him all season to take the title at the last minute, and by one point. So, when Archer beat him too, it convinced the Aldershot lad to do the series in 1956.

Asked if he would have considered joining a works team Les said he’d never been officially asked by anyone, but in any case he’d only ever really wanted to ride Norton. He added in the Bashford interview some of the supposed works preparation had left him mightily unimpressed too, which was another reason for sticking with the Nortons built at the family business and racing as a privateer. That said, there are privateers and ‘privateers’ and Les was clear to praise the help he did receive from the Norton factory where the racing department gave his team every assistance it could in the form of special engine and gearbox parts.

An unlikely machine

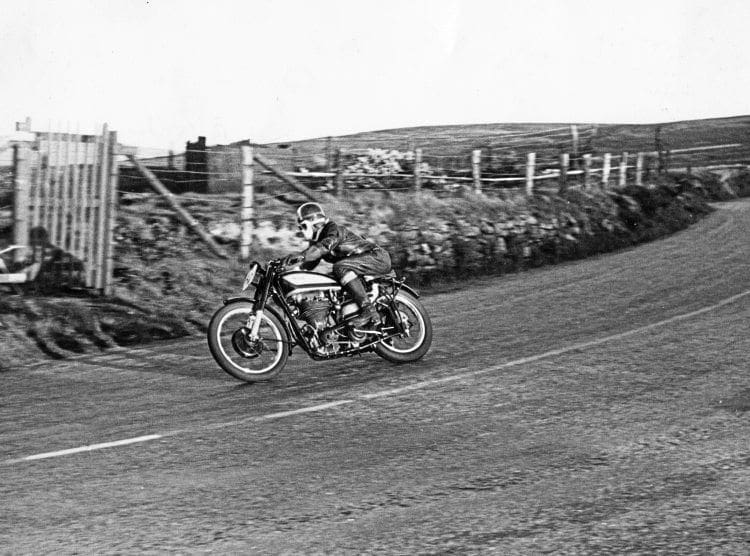

Though a road racing machine might seem an unlikely start to scrambling success, in Ron Hankins’ workshop the Manx Norton has become a commendable off-roader. Or, more correctly, the engine (and a long-stroke one at that), fitted into a frame inspired by Norton’s own Featherbed one, has done it. It is possible to assume, and it has been said, the frame started life as a Featherbed and had been altered, but the truth is Ron Hankins built a jig to make his own frame.

Though our story ends with the 1956 championship, Les Archer raced Manx-based machines up until the mid 1960s except the last one, with frames taken from Hankins’ jig. To construct the frame, from legendary Reynolds 531, a Featherbed inspired bottom loop was bent up but mated to the steering head in a sweeping curve to allow a larger front wheel to have enough travel for a motocross event. In order to cope with the increased stress on the steering head in a scramble, Hankins welded in plenty of bracing. Such efforts to make a bike as it should be did not go unnoticed and with Archer winning there were grumbles the bike was too specialised and certain people petitioned to have it banned – sour grapes maybe? It was claimed to be for the good of the sport but had Archer circulated at the rear of the entry would he have caused such a fuss with a special frame?

Though eventually the frame would house a fairly potent Ray Petty-built motor based on the double overhead camshaft unit, for the 1950s it was the single overhead camshaft version which did the business. Gear ratios

to convert this power to the back wheel, incidentally a Manx item too, were arrived at by careful study of the Manx spares lists. Les felt the big advantage of his Norton over the opposition was its power to weight ratio and its balance as Ron Hankins had tried to provide a neutral balance to the bike with its balance point at the footrests.

Speaking to Venables in 1956, Archer said the maintenance schedule for a machine even then as old as his, was quite high and added BSA’s Gold Star was producing a little more power but lacked the suspension development and meticulous preparation his Norton had. This meticulous preparation is a Hankins’ Hallmark and knowing his machine will be away from his care for long periods Ron makes sure it will be as reliable as possible. Les told Venables Ron had taken care to find out fuel quality in various regions and tended to set the compression ratio as high as possible for what he expected Archer to be able find in the way of petrol. If fuel quality is known to be poor then down comes the ratio.

Though as Les said he was never a works rider but merely closely associated with the factory, there were discussions to produce an over-the-counter Archer Norton replica. This came to nothing though as road racing was ‘king’ at Bracebridge and scrambling seen as having publicity value but still a dirty sport. However, the real reason was likely the calculation of a production version costing over £400 which was close to the Manx racer’s cost in the mid 1950s.

Norton were, however, keen to exploit all avenues and supplied a Dominator twin for Les to try around about 1954. Fitted into the Hanks frame Archer recalls it being a worthy performer but not to his taste and he didn’t ride it often.

Archer’s day

Though the majority of the 1956 series warranted only small reports in the UK press, the British GP covered a spread in The MotorCycle, headlined ‘Archer’s Day. Quite rightly so, as he dominated the GP by winning both heats to wipe out any doubt cast by his early season problems.

No less than 15,000 people went along to Hawkstone Park in Shropshire where the Salop club laid out a course to put the accent more on rider skill than sheer speed and also allowed for a greater spectacle for the paying public. Rain early in the morning ensured the track was in prime condition for the international event later in the day.

Going into the meeting it was Geoff Ward – BSA mounted rather than AJS – and Belgian Nic Jansen sharing the title lead. Behind them came six riders on eight points including Archer and the reigning champ Draper.

Ahead of them all were two heats of 10 laps on a recognisably tough course. To kick-start the day were two heats and a final of a 500c invitation race to whet the spectators’ appetites and they got to see PN Taft, described as an up-and-coming youngster, dominate the race giving the crowd a taste of what was to come with Archer.

With all due pomp and circumstance the field of international riders paraded before the home crowd then took their places on the start line. A false start showed how nervous the entry was but the restart was clean with Belgian Rombauts taking the lead from Britain’s Geoff Ward. Our man Archer managed to pull alongside Ward then by the time the entry completed the first lap Les had the lead and increased the gap between himself and Rombauts as the race progressed. A collapsed rear suspension unit slowed the Belgian in the latter stages of the race and allowed Ward to pass and by the last lap third place was over to John Draper and all eyes were on the second heat. Before then though there was an interval where the 1000cc invitation race took place which gave riders a chance to rectify their machine problems.

For the second race, Archer and Ward surged ahead of the pack and things looked good for a British domination of the second race too. Unfortunately Geoff Ward’s BSA suffered fork trouble… they were jammed on full depression! There was little option but for Ward to retire. His second place was taken by Rombauts – for a while – until he hit problems again and Nic Jansen assumed second, but with John Draper hot on his heels. Draper passed the Belgian but Archer was steadily pulling away from the field with a 20 second lead – a long way at such speeds. In the end his lead was an unassailable 38 seconds, putting him top man of the day and moving him to joint first in the championship with Jansen, both having 16 points. An excellent day for Archer and the UK. ■