In 2016, Brian Catterson, former editor of Motorcyclist, was at the CZ World Championships when he decided that a Husqvarna version was needed and similarly deserving.

Words and pics Norm DeWitt

Southern California was the hotbed for all things Husqvarna in the mid-1960s, given the efforts of Edison Dye, a number of Swedish racers (Lars Larsson, Gunnar Lindstrom and Torsten Hallman) and a few early devotees such as Malcolm Smith.

By 1970 the movie ‘On Any Sunday’ was being made, which upon its 1971 release, exploded the sales for all things Husqvarna at the very end of the four-speed era. Given the above, in March 2017 the Husky World Championship was held at Cahuilla Creek MX Park in the high desert near Anza, California.

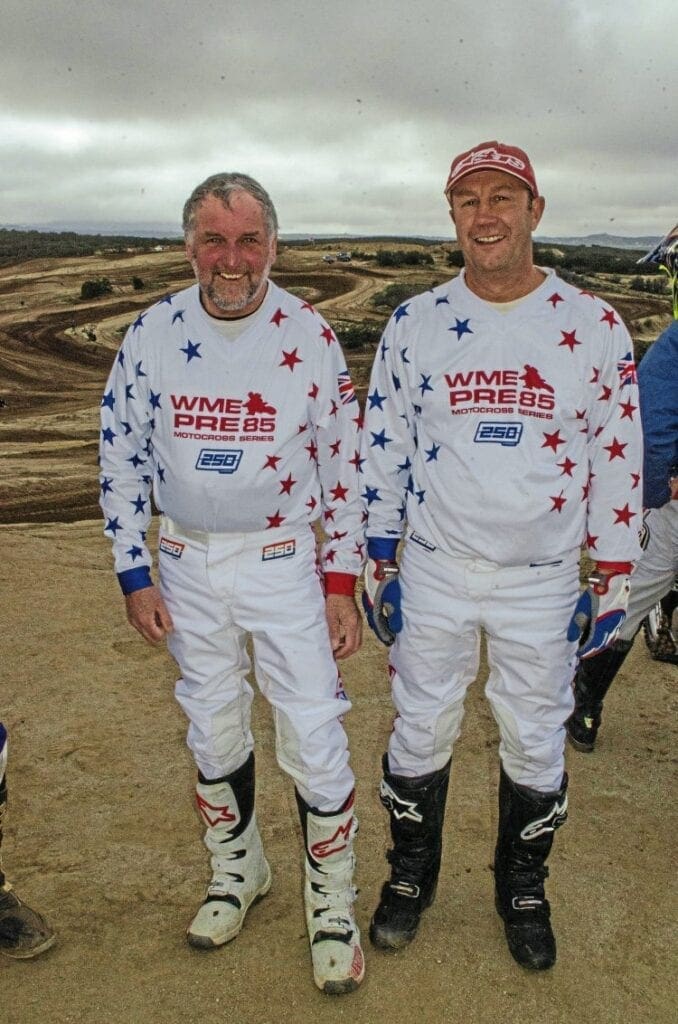

Riders arrived from all walks of life and all parts of the globe. From the UK arrived Team UK, their four-rider effort being provided machines by Tom Contino at TMC.

The team was also known as Team Nigel Mansell (after the F1 World Champion), because one rider was Nigel Green, and another Paul Mansell. They looked like Evel Knievel in their white star-spangled outfits, plus having a union flag on the sleeves.

Ric Field came by way of South Africa. Ric had seen Malcolm Smith riding a Husqvarna in the 1976 Roof of Africa Rally, Ric immediately then getting a 250WR to race.

For his 60th birthday, his children sent him back with 10,000 dollars to visit South Africa to pursue his other passion, surfing.

Turned out the National Scrambles were there at the time and the locals provided him with a bike, all being 99% sure it was his old race bike, a 1976 250WR (very rare in South Africa).

“I nearly fainted when I saw the bike,” exclaimed Ric. Ric won the 60+ class with it that day – now living in Denver, Colorado, his white/blue alloy tank 430 is one of the 13 Husqvarnas he currently owns, not counting the vintage bikes he exports to the UK.

Some of the racers were highly accomplished, others were anything but. Robb Mesecher brought ISDE experience (1989 Germany and 1990 Sweden) and he had brought an armada of beautifully restored machines, with a rare blue 125WR being one of the nicest bikes in the paddock.

Chip Howell, 1981 ISDE gold medalist and former Husqvarna factory rider, brought not only the 390CR he had raced for the factory, but his 1979 season mechanic Don West was there spinning wrenches just as he’d done 38 years before. Chip was to win the 1974 and earlier races, sweeping both motos with his 1974 400CR.

Professional racer Ben Meza strapped on a Jofa and put on a shocking display of style and speed on a 390CR in the 1975 and up vintage class.

A stroke of luck was that I had brought a trunk full of 390 parts to sell at the event and those parts kept both Chip and Ben running after each had 1st moto mechanical failures, Chip losing a rear axle nut and Ben losing a chain when the swingarm mounted guide broke.

Thinking of Wimpy (Popeye) for inspiration, I accepted payment from Meza by way of a hamburger.

There were a few truly special bikes in attendance. John LeFevre of Vintage Husky brought his titanium-framed bike that had previously had a four-speed engine which had been raced by Gerrit Wolsink.

Next to that was another original factory rarity, a chrome moly race frame bike, this one a 125. Gunnar Lindstrom had brought his 1957 175cc Silverpilen Husqvarna that in many ways was a significant step in the development that ended with the 1969/71 400 cross.

Mega-collector and race announcer Tom White provided a very unique 1967 250cc Swedish Army bike that Lindstrom confirmed was to provide the basis for the later 360 Sportsman.

In developing the 250 Army bike, Gunnar would ride it the 100 miles to Rolf Tibblin’s house where the two would train together, and then Gunnar would ride it home.

The honoree of this Inaugural Husky WC was 1971 US 500cc Champion Mark Blackwell. Mark being the first 500cc American champion, achieving this on a Husky 400, it was fitting that he would be the first racer honoured by this event.

The event was a success and thankfully the California storm gods decided to hold the weather off long enough to allow the event to proceed during an otherwise drenching winter. Long may it continue…

Silverpilen on top of the world

For such an inauspicious start to a motorcycle line the confidence displayed by those involved in it was rewarded by Torsten Hallman in 1962 when he was crowned world 250cc champion.

Our photo of him here in action on his Husqvarna was taken during the British 250cc GP at Higher farm near Glastonbury in Somerset when Hallman had to accept an overall second place to a superbly on form Dave Bickers.

The MotorCycle of July 1962 carried a full report of the 250 series, newly elevated to world class status. Much was expected of the works BSAs ridden by Smith and Lampkin but as first practice in this slickly organised event got underway it would be apparent to all the tussle would be between Bickers and Hallman who both excelled in the dry conditions.

An indication of the future was given when for the GP of the 37 starters only four were on four-strokes. In the first heat – the GP consisted of two heats – Bickers hauled away from the field and had a lead of six seconds over Hallman by lap five and Hallman himself was 14 seconds ahead of Czech rider Vhlastimil Valek.

These positions were maintained to the end. For the second heat Hallman blasted into the lead with Valek on his tail. Bickers had other ideas though and fought through from third to take the lead from Hallman on lap five.

In the end though Hallman’s two second places were enough to propel him to the lead in the world championship and eventually see him lift the title.

The Husqvarna Silverpilen 175 – daddy of the line

The entire history of Husqvarna in off-road racing can be traced back to a street 175 that was built to put the teens of Sweden on wheels.

Gunnar Lindstrom spent 10 years of his career in those early days at Husqvarna, being amongst the first Swedes to race in America (second only behind Lars Larsson) and helps to chart how this bike provided the genesis of all their subsequent MX success.

Gunnar: “The bike was the start of Husqvarna in successful racing as we know it. Husky was strong in 1934/35 with the V-twin racers. That never led to sales of V-twins, sales were abysmal as the numbers were in the hundreds.

“After the war they changed direction entirely. They had a little 98cc two-stroke pedal bike, purely for going to work. Those were the days when you lived near where you worked. By Swedish law, a 98cc with pedals had lenient insurance and a light driver’s licence requirement.”

“They (Husqvarna) wanted to move up from the 98 and they had something called The Dream Bike. It was a classic European flavour of bike with streamlined frame and they didn’t sell.

“They said ‘we need to have a racing version, we need to compete!’ So they built a sport model of The Dream Bike with two exhaust pipes up although the engine was pretty much the same. They won the six days big time in 1953 or 54, but it didn’t make a difference, nobody cared how many victories you had.”

“They were at their wits’ end and so they said, ‘this is what we are going to do. There is a law in Sweden that says under 75 kilograms in weight makes it a lightweight and 16-year-olds can get a licence to ride it.’ Over 75kg, you needed be 18 and to have a driver’s licence. The Silverpilen 175 came out in 1955 and was a huge success as kids 16 years old got their licences and bought thousands of bikes per year.

Gunnar: “Then they built a 200cc version with just a bigger bore. For some reason that thing never became popular; for some reason it got the reputation as not being as reliable, or not being as good. The 200cc version was called the Goldenpilen (Golden Arrow), gold and black was the colour scheme.

Otherwise, everything was the same except for the cosmetics, as the Silverpilen was silver and red. They were sold up until 1962, I don’t think they were made any longer than 1960, as they were selling from existing stock for two years. By that point there were enough bikes in the used market for new riders, so they didn’t sell as many.”

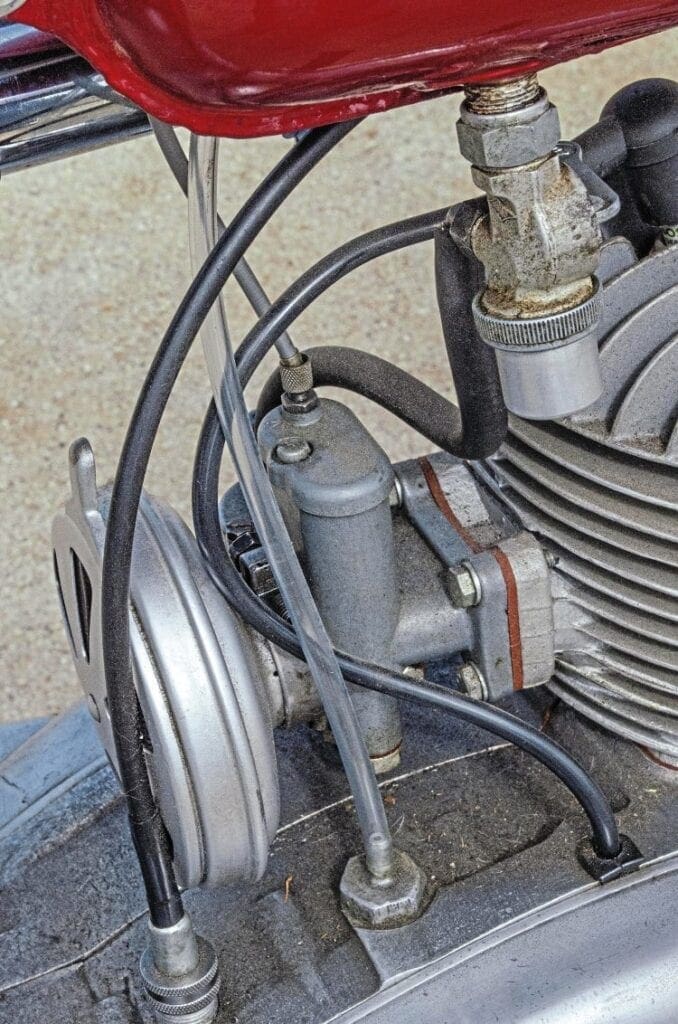

The shocks are moved up on the swingarm on the Silverpilen, but when it came to building their GP bikes, Girling shocks went way back to a conventional position on the swingarm.

Gunnar: “That’s the irony. That’s the first bike that had the laydown shocks (Gunnar’s 1975 360CR) after the Silverpilen had it. The first one was to save weight and have a shorter shock by moving it forward with less metal, and of course on the 1975 bike it was purely for travel. Strange things happen.

“Some of the things which stood out at the time, was that the Silverpilen had an aluminum cylinder with a chrome bore, and the pistons came from Mahle or KS… there were two suppliers that provided pistons from Germany at the time.

“And the reason we didn’t build bigger bikes like 250s is that there weren’t any pistons. Husqvarna had a good ‘in’ with Mahle in particular because they supplied cylinders and pistons for the chainsaws.

“The chainsaws had to be extremely lightweight and so they did the same thing, they had aluminium cylinders with chrome bores. That’s how we got Mahle to do stuff for us, where other brands didn’t have leverage as we did.

“The chainsaws were made in the 10s of thousands. Piston availability drove the development of the two-stroke motocross bike.

“There weren’t any handy carburettors that could work and pass the test for dirt riding. This carburetor has two slides right next to each other, 2 x 18mm. The first slide goes up to about three-quarters of the way and has a little hook that then lifts the second slide as well.

“It essentially had secondaries like a four barrel carb. You’d have the torquey bottom end without sacrificing the top end.

“It worked great but it was kind of hard to twist it as you had two springs and two slides to pull and it was never really easy to ride. Soon the 32mm Bing came out, with one main jet, one slide… with half the complexity. We all changed and bought manifold adaptors.

“At that time there were discussions about these bikes being modified for off-road. The internal debate was with all the negative stuff first. ‘Aaah, the tyres won’t even fit. You guys work over here and we don’t know what you guys are doing because if it goes wrong the factory cannot stand behind it.’ It was an unauthorised division with a small group of really enthusiastic guys.

“And in the factory the project was really popular. When it comes to case hardening some shaft or a crankshaft case, we’d show up with ‘here’s the new shaft for the sewing machine’, and they’d all go ‘oh yeah’… as the sewing machine or chainsaw divisions would pay for the work. There was a lot of creative accounting going on at the time in the late 1950s and early 60s.

“The conversion to an off-road bike was successful. We had Girlings in the back but the front fork was a huge issue in Europe at the time. Earles forks were used because we could build them and we could control getting parts like the Girlings.

“The only forks you could get from England were either Matchless or AJS… big heavy things. The lightest one was the Norton Roadholder. This was before Sten Lundin met Mr Ceriani in Italy somewhere, and he then introduced Hallman to Mr Ceriani who made a small lightweight version for the bike, as Torsten didn’t like the leading link forks that we had.

“The 1963 250 bikes we sold from the factory had used the Norton Roadholder forks from the street bikes. I used those Norton forks for a year and never had a problem. Of course we had no idea what we were doing with forks and damping… if they didn’t bottom it was good.

“If it did, we added more spring at the top. It was so rudimentary at the time. We had two years of Ceriani but then when things didn’t start showing up on time we decided we needed to build our own forks.

“The early engines were made really torquey as we only had a three-speed transmission at the time. The four-speed didn’t come until the prototype for Torsten had it in 1962. The whole transmission is a Mickey Mouse concept that came from the moped, which was a two-speed.

“To the left was first, to the right was second, and then they added very small diameter dogs to the middle of the shaft to capture a third gear. Eventually that was what they made a four-speed from, and it was amazing that it worked from a metallurgy or design aspect.”

The modified four-speed Silverpilen transmission won the 250 World Championship in 1962 and 1963 with Hallman aboard. The 500cc class was another situation entirely.

Gunnar: “The 360 engine highlighted the problems with the transmission. From the beginning, 360s were built as that was what you needed to get into the class (351cc min). But after a while the CZ people were leading with their 360 so we had to pump the power up a bit.

“The factory did not trust the transmission and built an engine with a separate transmission. Three bikes were built and they were a huge disappointment. The engine was too wide, vibrated, and the transmission chain was so hot it was glowing.

“Torsten actually forced the issue and had a friend weld together a 360 top end to a 250 crankcase and it lasted a lap so they decided to build a real 360. They later used that same transmission on the 400 and the 500 twin. When Aberg and Kring were winning everything with the 400, people were paying hundreds of dollars on top of the retail price, to buy bikes and have them flown to America.”

The oval case Husqvarna transmission and case used during their Golden Era (through 1971) had been a direct development of the 175 Silverpilen three-speed. The factory forgot the lesson of the Silverpilen when it came to the new 1972 production bikes.

Lindstrom: “From the design perspective… in development if you don’t have anything to meet, everything is over-done, overly safe where you want to eliminate anything that could possibly go wrong. If you start with a little bike, upsize it and fix what breaks, you will end up with a better product than if you try to downsize it.

“That’s what happened in 1972, when the 450 Desert Master came out, the big engine five-speeds. Long story short, those were designed from the other end.”

Leaning heavily on their World Championships, desert victories, and the enormous success of ‘On Any Sunday’, sales exploded but these subsequent production machines were never to obtain the same reputation or results of the earlier four-speed models.

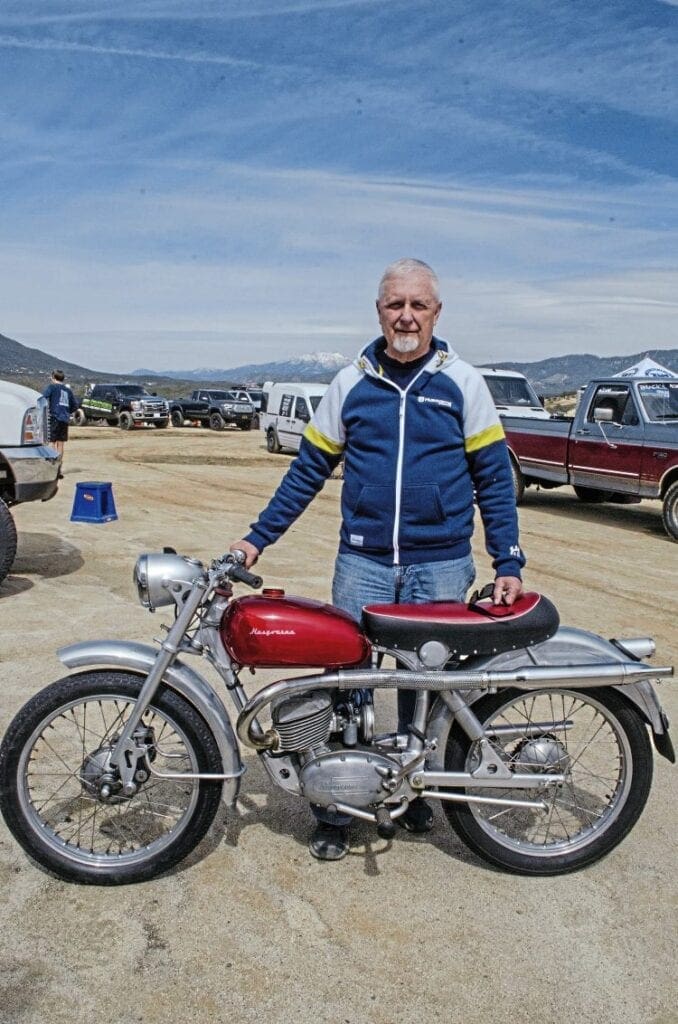

Gunnar Lindstrom brought his 175 Silverpilen to show at the Husky World Championships near Anza in Southern California.

“This particular bike, a friend of mine has used it for his daily transportation in Sweden, he is the third owner from over there. It was still on the road, he rode it for vintage events, fun things, and occasionally to work. The bike is non-modified… it’s restored, but is a non-modified Silverpilen (Silver Arrow) in the way they were… the way they came.

“The friend that sold it to me did the restoration and the good part about this thing is that there’s not a whole lot of new parts other than the exhaust pipe. The fenders and everything are still original and you can see it’s got all the scuff marks but it’s been polished up.

“Some of the holes in the aluminium fenders had pulled through. Aluminum and vibration don’t go good together, at least not on the Silverpilen, that’s for sure (laughs).

“I needed one for my collection. I don’t have a big collection, but I needed one to put in the living room frankly, so that’s what that bike is for.”

No doubt that Gunnar has some serious motocross history on display, as without the Silverpilen, none of Husqvarna’s off-road championships would have transpired.

Read more News and Features online at www.classicdirtbike.com and in the latest issue of Classic Dirt Bike – on sale no